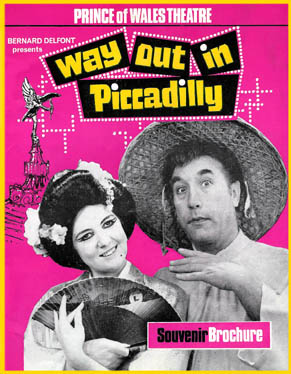

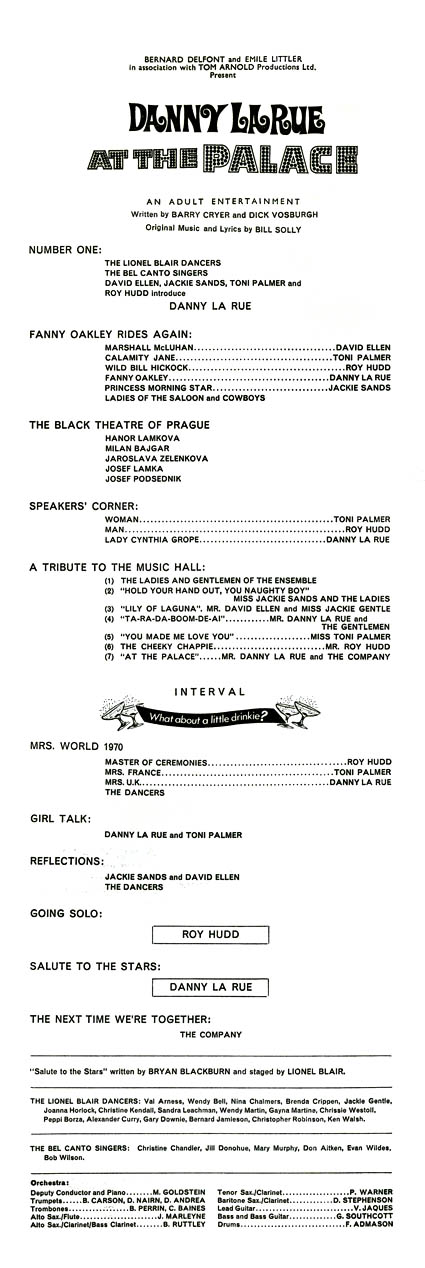

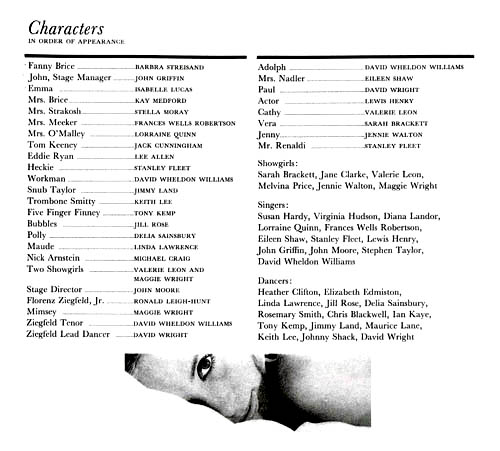

From 1963 whilst Assistant to Bernard Delfont (who presented The Royal Variety Performance from 1958 to 1978)

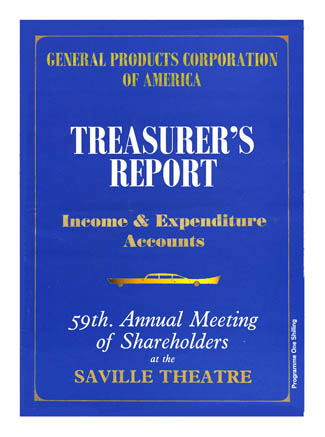

General Manager and subsequently Director of Bernard Delfont Limited, the Company

managed

from time to time: The Shaftesbury, The Royalty, The Saville, The Palace, The Coventry Theatre, The New London,

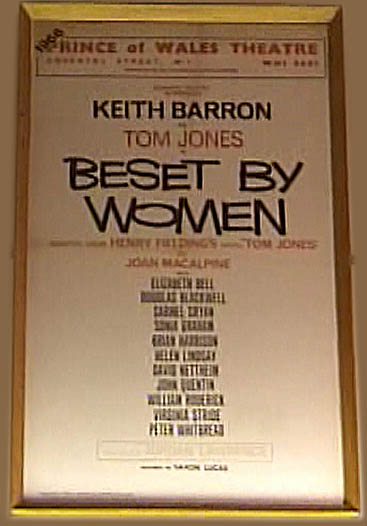

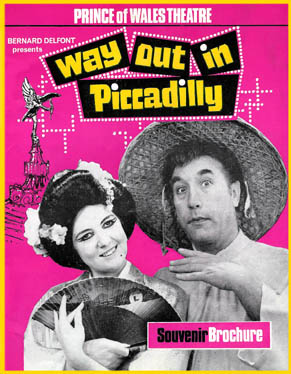

The Comedy, The Prince of Wales, The Casino (later The Prince Edward) theatres:

ran the Talk of the Town and presented the following productions:

|

|

I started to work with Billy Marsh on 21st January 1963. Sitting in the same office as him was an education in the world of light entertainment. There he was, seated behind his enormous desk, a very slight stooping figure, very quiet, a cigarette permanently drooping from his lips, the ash cascading all over his jacket; (in fact, there was so much of it about, it felt as if I was back at the Wyndhams Theatre, raking out the boiler); very secretive, relatively unsocial and with a brilliant mind. Ruthless in business but away from it, was kind and gentle.

Among the many clients who Billy represented were Morecambe and Wise. Eric Morecambe said, ‘When I die, I would like to be cremated and have my ashes scattered on Billy Marsh’s jacket’. When Billy died, his request that he be cremated, and his ashes interred at the London Palladium was carried out. They were bricked up in a wall behind a ‘No Smoking’ sign. Later on, Paul Daniels pointed out to me that MR ASH is an anagram of MARSH.

Billy’s office overlooked the Haymarket; the furniture was minimal; a settee, some chairs and his very large desk. I sat opposite him at the desk with one phone at my disposal. He had three, plus an intercom to the rest of the offices which housed Keith Devon, a director of the agency, and Glynn Jones, an ex-road manager, who kept an eye on the artists’ requirements at the Talk of the Town, and was general gofer for the office, Keith Devon and several of the Delfont shows.

Glynn was a character, who had worked with some of the great Hollywood names as a road manager. His office was an armchair in Keith’s office. Since he wasn’t a great organizer, his filing was kept under the cushion

Among the other members of staff was Roy Mosley, an up-and-coming and very keen young agent who worked with Keith. Jack Ingham, who was previously the theatre critic on the London Evening Star, was in charge of publicity. There were miscellaneous secretaries, accountants and Douglas Harrison, who was a director of the company was in charge of accounts. Dougie was very astute and known throughout the business as a late payer. He considered he had failed in his duty to Bernie if he paid any accounts on time. Robert Nesbitt, the creative genius of the Talk of the Town, along with his very efficient and pleasant secretary, Rosalyn Wilder were based in a different building in Cranbourne Street.

The day always commenced with me under the eagle eye of Billy, opening the telegrams which came in code from all the Delfont shows in London and the provinces, deciphering them and entering them into a large red bound book known as ‘the figures book’. The code was 'Cumberland' - 'C' standing for 1, 'U' standing for 2, and so on. I don't think it would have been too much of a test for the wartime code breakers at Bletchley Park.

One day we received a telegram from one of our venues, which read 'C minus 1'. This completely baffled me, so I phoned the theatre in question and found out we had to cancel the performance that night. I would read the results over the phone to Bernie, who was based with his secretary Lena Gaston at the Prince of Wales Theatre. Then came the ceremony of opening the post. Every piece of correspondence always came to Billy’s desk first. I would open it, date stamp it and pass it over to Billy, who read everything. We then sorted it into piles, and distributed it to the various departments.

Nothing but nothing passed through the office without Billy seeing it first. Bernie was ultra cautious, ever since one of his previous chief accountants prior to Dougie, had embezzled a large sum of money, and had also emptied Bernie’s personal safe deposit box to which he had the keys.

Part of my learning curve was to sit opposite Billy, and learn how he put the light entertainment shows together; how they were balanced and how running times were allocated. This was relatively easy to pick up since, given that you had a big star attraction, which we always had, due to Billy’s wheeling and Machiavellian dealing, and the fact that he and Keith Devon represented a large percentage of the most important light entertainment stars.

Applying the right mix of supporting artists, their time and place in the running order, was more or less routine. I also had to listen and observe how he dealt with his stars; Morecambe and Wise, Frankie Vaughan, Norman Wisdom etc., etc. This although interesting, was not crucial to me, since it was never my intention to become an agent, but at least, it did give me a chance to back up Billy, in the unlikely event he was away from the office.

I was also assisting and advising Bernie on certain elements of his musical and legitimate productions. At lunchtime, I used to meet up with my friend Peter Charlesworth, have a quick lunch at Gerry’s club and go round the corner to the Empire Snooker Hall to have the odd game.

Peter, with whom I was to have many adventures over the years, was already quite a character. He told me about one of his early escapades in the 40s. He managed by some nefarious means to get hold of a dozen eggs which were in extremely short supply. Thinking he could make a few pounds on the black market, he sold them to a chef at one of the London hotels and was suitably recompensed. A little later he managed to obtain some more eggs, so he returned to the chef to offer them to him who said: 'Oh - it's you is it? That last lot of eggs you sold me were all hard boiled. Can I have my money back please?" Peter beat a hasty retreat clutching his eggs like a broody mother hen.

We used to play two-handed poker and when we played at his flat, even if we finished at 7 o'clock in the morning as I was bidding him farewell, he would already have the vacuum cleaner out and be hoovering the entire flat.

He could sometimes be a slow payer - in fact, he was so slow that when we played at his flat I used to say: 'Do you mind if I take away some of your antique guns as security until your cheque has cleared?'

Later on I insisted we both played for cash and in the 60s we used to meet at my flat, both having drawn out £5,000 in cash, change it into chips, putting the cash on a high shelf and then when one ran out of chips - the game was over.

I always used to cook him a meal prior to the game with the finest filet steaks, vintage champagne and Napoleon brandy - trying to ensure that he was pissed. However, I drank just as much as he did - so I guess we were both pissed. One night, having won all the money I said: 'the only way you can get out of trouble is if we go to a casino called The Pair of Shoes and play blackjack.' This we proceeded to do. He was so drunk - he could hardly sit on the stool at the blackjack table. The rest of the evening passed in a haze.

I think I left before he did but he told me when he woke up the next morning with the most terrible headache, he blearily opened his eyes and found his entire bedroom festooned in five pound notes. Apparently he had a tremendous win but he was so drunk - he didn't realise it.

He has never married, but he has always been keen on the fair sex. The younger - the better. In the 50s he was going out with eighteen year old girls. In the 60s and 70s he was going out with girls young enough to be his daughter. In the 80s and 90s - his granddaughter and as I write this - young enough to be his great-granddaughter.

His gambling has also increased in direct ratio to the age difference between him and his girlfriends. He has become a legend at the Victoria Casino where he he has been known to frequently to wager £25,000 on the turn of a card. Although this sounds a lot, he doesn't throw his money about. In fact, when he gives a £1 tip to a waiter, it is as if he were bestowing a benediction.

Good luck to you Peter. You are one of the great characters it has been my pleasure to know over so many years.

The Empire which had about ten snooker tables was owned by one of the Ganjou brothers of the famous adagio act, ‘The Ganjou Brothers and Juanita’. It was always jammed full of variety agents and acts - in fact more business was conducted there than in the offices.

Years before, Lew, Leslie and Bernie all used to spend a great deal of time there, but now they had grown too grand. When Bernie was struggling, he ran up a bill of several pounds for snooker table time (they used to give credit). When George, the manager, pressed him for the money, Bernie couldn’t pay, but he had a solution. Among other things, he was running the entertainment at the Locarno Ballroom in Streatham; he said to George, ‘Come next Wednesday night, make sure you’re dancing when we have the Spot Waltz prize, and I will see that you win it.’ He did.

Early on while I was with Billy in the summer of ‘63, Arthur Haynes, who was starring in ‘Swing Along’ at the London Palladium, was suddenly taken very ill, and Bernie asked Billy if he could persuade Tony Hancock to take over.

Billy arranged for Tony to come up to the office. The three of us sat together, me merely as an observer, watching Billy using all his powers of persuasion, trying to get the extremely reluctant Tony to agree to take over. ‘There is one extremely important proviso’, Tony said, ‘and that is, that I do need for my self-confidence, an awful lot of rehearsal in a theatre – but I don’t want anybody to hear or see me rehearsing. I must have your guarantee on this’. Billy said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll sort it out’, and Tony left.

Billy and I pondered this, and came up with the idea that each night after the show had finished at the Prince of Wales theatre, and everyone had left, we would leave the curtain up with some working lights on stage. We would lock Tony in, so that the only other person present in the theatre would be the fireman, who had strict instructions to hide himself. To our surprise, Tony happily agreed to this, and every night he was locked in the theatre and rehearsed to his heart’s content, until such time as he felt tired. In the early hours of the morning, he would then summon the fireman, who would unlock the stage door and let him out.

After a short time, Tony announced he was ready, and he happily took over at the Palladium. His act onstage fell short of the triumphs he achieved with his various TV shows.

It seemed to me that it was about this time that the slow disintegration of his career gathered pace. He had previously divested himself of the people who had been such a solid support in his rise to fame, Bill Kerr, Kenneth Williams, Hattie Jacques, Sid James and finally, his writers, Galton & Simpson and Beryl Vertue, his agent. He desperately wanted to be a success in films, but this was not fulfilled, and this, together with his dependence on alcohol, created a downward spiral in his self-confidence, unfortunately manifesting itself eventually in his suicide at the age of forty-four in Australia in 1968.

What a tragedy; one of the all time greats of television, dying so young. My own personal recollection of Tony was that he was extremely polite and pleasant, certainly as far as I was concerned.

TONY HANCOCK QUOTE: "It's red hot, mate. I hate to think of this sort of book getting in the wrong hands. As soon as I've finished this, I shall recommend they ban it."

I had known his brother Roger, (who subsequently became an extremely successful agent), from the early ‘50s, when we both used to spend a great deal of time at the Player’s theatre. On one occasion, we were offered the part of the pantomime horse at the Player’s Theatre club, but I declined, since Roger insisted on playing the front end. We were both almost the same age and there was a remarkable likeness between us – in fact on occasions, we were mistaken for twins, (perhaps either his or my father had a fast bike). Some years later, I had an extremely bizarre conversation with a young lady; it took me a few minutes to work out that she was one of Roger’s ex-girl friends from years before; she thought she was talking to him.

Whilst during the day I was sitting opposite Billy in his office,in the evenings, I was still working on ‘Come Blow Your Horn’ at the Prince of Wales theatre. This was not an onerous task, and I sometimes had a half an hour nap in my dressing room whilst the show was running. (Years later, Michael Crawford, whose dressing room was next door, accused me of always being asleep).

There was a good reason for needing these naps, because as soon as the curtain came down I would depart to Crockford's Casino, or Charles Palmer’s house to play poker until the early hours of the morning - sometimes until 6 a.m. I would then drive home and go to bed, even if it was only for an hour, prior to getting up to be in time for the office. This as you can imagine, resulted in me having rather red eyes, but enter Shirley Eaton, who gave me a tip: ‘use some eye drops called Couleur Bleu’. This did the trick - my eyes immediately cleared.

Through this lack of sleep, I felt as if I had become something of an expert on the subject of dreams. It seemed to me that dreams were a subconscious way of clearing out the filing cabinet section of the mind - getting rid of all the unnecessary information that was clogging up the works. It didn’t matter how little sleep I had, the dreams seemed long and vivid. It was as if my mind knew it only had a short time to get rid of the extraneous information, and it went into overdrive. I was able to continue like this for some months; although my body was tired, my mind seemed to be refreshed.

‘Come Blow Your Horn’ finally closed in May of 1963, so I was able to play poker in the evenings and still get some sleep. I was also able to spend more time at the Talk of the Town in the evenings.

The format of the Talk of the Town was dining, dancing to a six piece band, a lavish, spectacular revue with a large orchestra, and a cast of about thirty-five, created and staged by Robert Nesbitt, running for about an hour; then more dancing, and finally, a big star, with a full orchestra for about an hour. The price of the evening’s entertainment plus food was only just over £2 to begin with - a great bargain - and we were always sold out.

Among some of the stars Billy had booked from 1960 up to 1963 whilst I was working with him were: Lena Horne, Max Bygraves, Sophie Tucker, Johnnie Ray, Francis Faye, Eartha Kitt, Frankie Vaughan, Shirley Bassey, Dolores Gray, Phil Ford, Mimi Hines and Jackie Mason - the latter was a then very promising up-and-coming young comic. Unfortunately, he was booked during the summer months when the room was full of Japanese tourists, and he sank without trace. Thereafter, the policy was to book singing acts only during the tourist season.

The most any of these artists earned was a basic £2,000 a week, with the chance to earn another £1,000 if we were full. The reason we were able to get them so cheaply was, because the Talk of the Town was the best and smartest venue in Europe; if anyone wanted the very finest showcase for their talent - this was it.

The Talk of the Town was the brainchild of Bernie and Robert Nesbitt. Robert was working in America, when Bernie asked him to fly over and meet him. Robert, who had been responsible for the overseeing of the development of one of the early Las Vegas venues, The Dunes, was extremely qualified to develop a high class theatre restaurant in London.

The plan was firstly to acquire the right theatre which could be converted. The Hippodrome theatre, which was located on the corner of Leicester Square and Charing Cross Road, was in a perfect situation and Bernie was able to acquire the lease from Prince Littler.

Then came the major problem - the money. The cost of the conversion and the production of the evening’s entertainment were going to be in the area of £400,000, (about £10 million at today’s prices). Bernie didn’t have it - in fact he didn’t have a tenth of it. Robert asked Bernie, ‘Where do we go from here?’ ‘Don’t worry’, Bernie replied. ‘I’m going to release a press story about this exciting idea of a theatre restaurant called The Talk of the Town, and I promise you, Charles Forte will be on the phone within twenty-four hours, asking if he can be involved’.

The press release was issued and received enormous coverage. Charles Forte was on the telephone to Bernie the next day, and suggested a meeting. At the end of the discussions, Charles had taken on the management of all the catering, put up all the £400,000, and Bernie was to receive a third of the profits. It was a very shrewd deal by two very clever men. Between them they created an enormous success, which ran for twenty-five years.

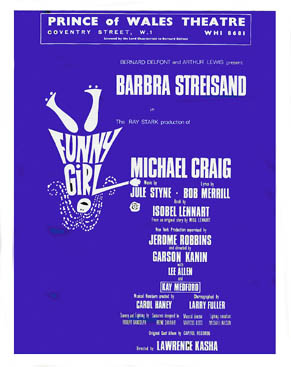

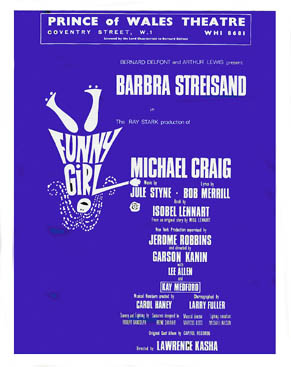

The show following ‘Come Blow Your Horn’ into the Prince of Wales was ‘On the Town’, starring among others, Elliot Gould, who asked Bernie if he would use his then relatively unknown wife, Barbra Streisand, in the next Royal Variety performance, which was due to take place later that year at the Prince of Wales theatre. Bernie promised faithfully that he would, but later on to his everlasting regret, changed his mind and used Susan Maughan instead. Not that Susan didn’t perform well - she was excellent. But Barbra Streisand !!!!!

The Royal Variety performance which took place on 4th November contained: Charlie Drake, Buddy Greco, Nadia Nerina, Steptoe and Son, Tommy Steele (who stopped the show, and forty-one years later at the Royal Variety Performance in 2004, at the age of sixty-eight, stopped the show again), Harry Secombe, Marlene Dietrich and the Beatles. When The Beatles came on to an ovation, John Lennon said, ‘Those in the dress circle applaud, those in the stalls, just rattle your jewelry’.

The Beatles were really beginning to take off that year, and the Delfont Agency could have gone with them. The previous year, Brian Epstein their manager, had a meeting with Keith Devon, and asked if he would like the sole agency of them, but would have to guarantee them £1,000 per week. Keith discussed it with Bernie, and they both agreed it was too much of a gamble. Oh well! You win some - you lose some.

Throughout the week of rehearsals for the Royal Variety show being there as a general dogs body, I watched enthralled as the master, Robert Nesbitt, put the whole thing together. He sat there on the centre aisle of the fifth row of the stalls, with a bottle of champagne and a glass on a small table at his elbow; immaculately dressed, and totally unflappable regardless of any problems. When it looked as if a major technical disaster was about to occur, Robert would just say a trifle tetchily, ‘I’m sure there’s a man somewhere who deals with this sort of thing’. And sure enough - there always was.

It was due to Robert’s genius at dealing with stars, that he was able to direct successfully over twenty Royal Variety Performances, with a minimum of major hiccups.

The final act to rehearse was Marlene Dietrich. Joe Davis could not make himself available on this occasion to do her lighting, so it was left to Robert Nesbitt, (known as the ‘Prince of Darkness’), who was just as good as Joe, to arrange it.

She appeared at 9 p.m; all the rest of the cast had gone home to get some well-deserved rest before the performance next day. The only people left in the theatre were Marlene and her pianist, the technical staff, Robert with his bottle of champagne at his elbow, and me sitting just behind him. The rehearsal dragged on and on; Marlene kept asking for the lighting and sound to be changed. Robert aware that the opening was not many hours away, was on the surface as unflappable as usual. ‘Yes, Miss Dietrich. Might I suggest - would you like to try it this way?’ Finally at midnight Robert said, ‘Do you think it would help things to go a little better if we had a glass of champagne. Richard, please pass a glass up to Miss Dietrich’. I duly obliged, and Marlene said, ‘Thank you. May I have one for my pianist?’ I took another glass down to the front of the stalls, and the pianist who had sat there without a peep for three hours, reached up and took it - it was Burt Bacharach. We finally made her happy at about 2.00 a.m. At the performance that evening she was sensational.

At the party after the show in the stalls bar, which was jammed end to end with celebrities, it seemed that nearly everyone, no matter who they were, just wanted the Beatles’ autographs. Nearly every time a photographer wanted to take a picture of The Beatles, Marlene introduced herself into the shot. The Beatles were very flattered by this attention from a superstar, but Miss Dietrich was extremely shrewd, and knew everything there was to know about publicity.

The following year, once I had learnt more about light entertainment, I was allowed by Bernie to play a small part in the selection process of the artistes for the Royal Variety Performance. This process first of all consisted of Billy Marsh, Keith Devon and me preparing a list of suggestions for Bernie. This list was added to by various agents putting forward their suggestions. Usually the most important of these were from American agents, since they would nearly always suggest headliners. There was furious lobbying from some of the agents in this country; ‘If you take (y), an up-and-comer, I’ll try and persuade (x) to star’. Not that they usually needed persuading, since it was the most prestigious light entertainment event in the calendar.

Once we had been through all the probables, it was then a case of evaluating a balanced running order; part of this took care of itself. There were always items with dancers and singers, usually to open the first and second half; then came the compere, then a specialty act, etc, etc, finishing up with the biggest star. Needless to say, there were occasions when star performers were peeved that they were not down to close the show when they thought they should be. Then finally, came the tricky part of allocating time.

Ideally, the entire show should take about two and three-quarter hours including interval, but most of the time this turned out not to be the case, as star acts overrun their time. On one occasion, the Queen was present when the show ran for nearly four hours. At the end of the show, Bernard Delfont took it upon himself to compliment the Queen on the beautiful dress she was wearing. ‘Thank you, Mr. Delfont’, she replied: ‘It’s the State Opening of Parliament tomorrow, and it’s so late, I probably won’t have time to change it’.

|

|

|

|

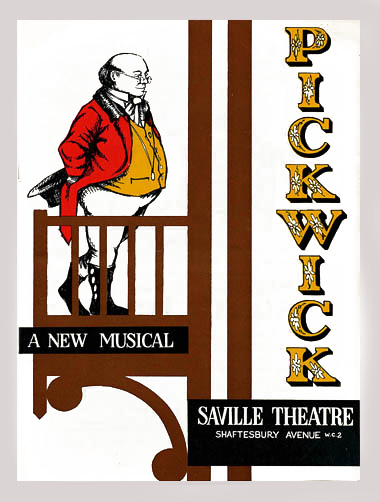

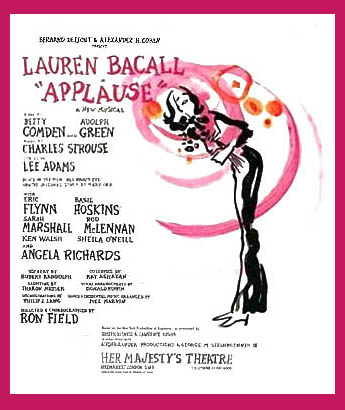

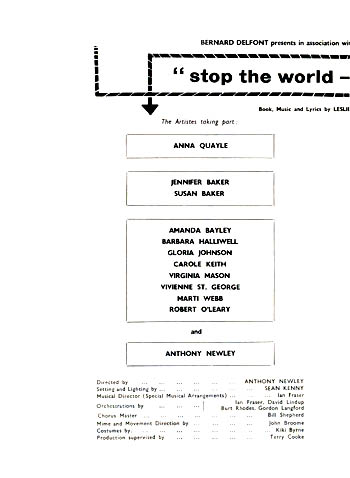

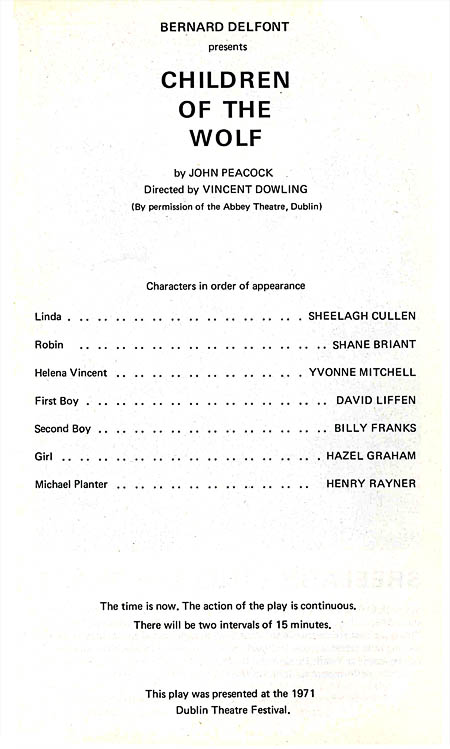

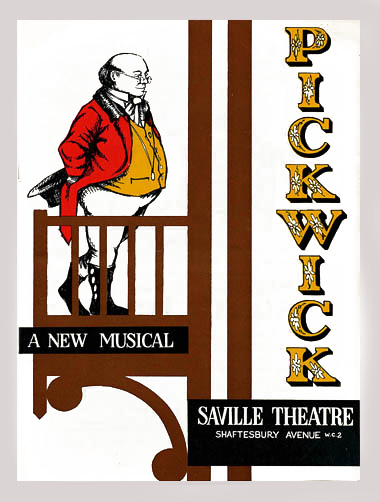

Apart from the tail end of the run of Stop the World, and its subsequent tour, the first musical I was involved in with Bernie was ‘Pickwick’which opened at the Saville, which was his theatre, on July 4th starring Harry Secombe. It was written by Wolf Mankowitz with lyrics by Leslie Bricusse, and music by Cyril Ordanel. The director was Peter Coe, and the designer Sean Kenny, who with Peter, had such a success with ‘Oliver’. ‘Pickwick’ was also a huge success, running at the Saville until February 1965. This was my first meeting with Harry Secombe, and everything I had heard about him was true. Without a doubt, he was one of the nicest people in show business. He needed to be, because earlier when he was doing ‘The Goon Show’ with Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan, he was the only one who could stop them from almost killing each other.

With Harry at the helm, the show was the happiest in London, with Anton Rodgers as Alfred Jingle, Peter Bull as Buzfuz, Teddy Green as Sam Weller, Jessie Evans as Mrs. Bardell, Julian Orchard as Snodgrass, Gerald James as Tupman and Oscar Quitak as Winkle. It was a wonderful cast; Harry kept everyone happy by throwing a party after the show once every four weeks in the stalls bar; he provided all the food and drink, and showed a film. Harry would prepare a list of films and ask the cast to vote on which one they would like to see.

The only problem that arose from ‘Pickwick’ was that Wolf Mankowitz had the idea of opening a new theatrical club in Cranbourne Street, called The Pickwick Club. Although it wasn’t very large, he persuaded Bernie to have the first night party there. It was like Dante’s Inferno when everyone tried to crush in. Half of Bernie’s guests couldn’t even get through the door, and those that did couldn’t find anywhere to sit, couldn’t get any food and just about managed to get a drink. To be fair to Wolf, he never anticipated such a large crowd. However, he pushed his luck when he presented the bill to Bernie for the party; he was told what to do with it in no uncertain manner. Bernie eventually settled for half.

Sean Kenny’s design for ‘Pickwick’ consisted of many large, tall, wooden platforms which had to be maneuvered in full view of the audience, by stagehands in costumes. There was the odd collision, but on the whole, it worked magnificently. One of the features of the set was a frozen pond on which Harry had to ice skate, then slip and somersault through a hidden trapdoor. It says a lot for Harry’s courage that in spite of his size and weight, he did this. I won’t say unflinchingly, because invariably he finished up bruised.

It was during the run of this show that I was to discover for the first time, the stupid intransigence of the Musician’s Union. At the opening of Act II there was a ballroom scene, and the music was supposed to be heard coming from upstage left of the scene, instead of the orchestra pit. I put it to the union that we could record the orchestra performing the music, and play it from upstage speakers, so it would sound as if coming from the ballroom. This would have given the musicians an extra fifteen minute break, on top of the interval. The musicians were obviously very much in favour of it, but the union said that under no circumstances could recorded music be played, even if it was the same musicians and would give them a break. I even offered them a recording fee, but they were adamant. Oh the stupid Luddite attitude of the unions in those days! Thank God it’s different in this day and age.

It was during this time that I first met Michael Sullivan, a sort of rogue agent, whom Bernie had decided to give a chance to, by allowing him to work within the Delfont agency. His office was literally the size of a broom cupboard; hence, he never met any of his clients there – it was elsewhere – usually in the bar of a hotel. Michael’s main claim to fame at that time was that he had discovered Shirley Bassey, but she subsequently left him for a new agent, Peter Charlesworth. Among Michael’s clients at this time were Dick Emery, Sidney James and Bernard Bresslaw.

Michael and l became friends and he reminded me of an incident which had taken place during ‘Come Blow Your Horn’. A young lady in the cast, Clare Gordon, was delightful but a bit of a scatterbrain – a sort of Goldie Hawn. She was invariably late in arriving at the theatre, and I constantly had to reprimand her.

On one particular Saturday it got to the half-hour of the first show and there was no sign of Clare. It then got to the quarter – still no sign. She’d never been this late before, so I was getting really worried. We arranged for the understudy to get ready. At the five minutes there was a phone call for me at the stage door; it was a doctor calling on her behalf, who said that she’d suddenly been taken ill, and she’d asked him to phone me. I got into a heated debate with him, asking why he hadn’t phoned earlier to give more advance warning. He responded by saying, ‘I don’t want to get involved in an argument with you. She’s too ill to phone herself and you ought to be grateful that I am calling you at all. I am a doctor – not a messenger boy’.

Michael told me that at the time he was having an affair with Clare; they were in bed together, and suddenly she looked up at the clock, and said, ‘My God – I should be at the theatre - I’m late for the first show’. Michael said ‘Don’t worry – leave it to me’, phoned up and pretended to be the doctor.

He was single at the time, having been divorced from his first wife. He had just become smitten with the French film star Dany Robin, whom he met when he was seated next to her on a London to Paris flight. She was married, but Michael pulled out every conceivable stop to woo her. He wrote to her, phoned her, sent her flowers and gifts, but nothing could shake her resolve not to get involved. He played his trump card when she told him that she was going on a cruise across the Atlantic, unaccompanied. He booked himself on the same cruise without telling her, locked himself in his cabin, and after three days at sea he suddenly appeared beside her at the ship’s rail, while she was gazing out to sea. That cracked it.

Eventually, she got a divorce, and they were married on 23rd November 1969. It was an enormous wedding; virtually everyone in the light entertainment side of show business was present. No expense was spared; a team of ten violinists played everyone into the reception. There were giant bears carved out of ice holding bowls of caviar; the champagne flowed unremittingly.

He had prepared a special comedy film of himself getting prepared for the wedding, which he showed to us all. At the same time, he showed us a ‘Candid Camera’ film which he had arranged, taken during they early stage of the reception, which most of us were on. He had a pretend waiter who kept coming up to us, interrupting our conversations, insisting on serving us things which we didn’t want, and not taking no for an answer. This resulted in some rather rude comments from the guests who were being pestered.

At the end of the reception, a helicopter landed, and Michael and Dany were whisked away to London Airport to get on a flight to begin their honeymoon – except that they didn’t. Michael had told me previously, that he wanted to hold a small, even more intimate reception for their closest friends, and he asked me to drive to his house once the helicopter had left. It was a good way to get rid of the majority of his guests and to continue the celebrations with a few intimate friends. I don’t suppose the guests would have had any cause for complaint anyway – they certainly had a marvellous time with unstinting hospitality. Just a small caveat - I’m not sure that Michael ever paid the bill.

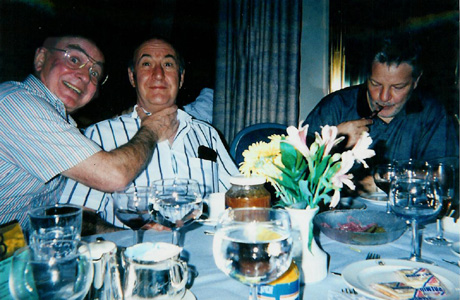

At The Lido in Paris - Dany Robin, Richard Mills,

Michael Simpkins (the lawyer) and Michael Sullivan

Prior to his involvement with Dany, we went out together a few times. One night, April Wilding invited me back to her flat at the Prince of Wales Drive, Battersea; April had a particularly attractive flatmate. I asked if she minded me bringing my friend Michael Sullivan; she said no, she didn’t.

We had a very good dinner, quite a lot to drink, and as the evening wore on we decided to play strip poker, with the winner claiming as his prize, one of the others. The girl I was particularly keen on was the flatmate. Michael was ambivalent, and the girl who had invited me was only keen on me. The flatmate wasn’t the remotest bit interested in me, so when I came to claim my prize as the winner, it resulted in an impasse, but it certainly helped break the ice on my first outing with Michael.

He thought I was lucky for him; he called me his lucky leprechaun and whenever he went to a gaming club, he would ask me to accompany him in order to bring him luck. If he won, he would give me some of the winnings.

|

|

|

| |

‘PICKWICK'

In order of Appearance:

...

|

Hot Toddy Seller |

|

Norman Warwick |

Cold Toddy Seller |

|

IAN BURFORD |

Turnkey |

|

Brendan Barry |

Pickwick |

|

Harry Secombe |

Roker |

|

Reg Grey |

Tony Weller |

|

Robin Wentworth |

Sam Weller |

|

Teddy Green |

Mr Wardle |

|

Michael Logan |

Augustus Snodgrass |

|

Julian Orchard |

Tracy Tupman |

|

Gerald James |

Nathanial Winkle |

|

Oscar Quitak |

Mr Jingle |

|

Anton Rogers |

Mary |

|

Dilys Watling |

Mrs Bardell |

|

Jessie Evans |

Rachael |

|

Hilda Braid |

Dr Slammer |

|

Brendan Barry |

Bardel Jnr. |

|

Terry Collins |

1st Officer |

|

Roger Ostine |

2nd Officer |

|

Norman Warwick |

Skater: |

|

Donald Graham

Joan Ismay |

Isabella |

|

Vivian St. George |

Emily |

|

Jane Sconce |

Fat Boy |

|

Christopher Wray |

Landlord |

|

Brian Casey |

Dodson |

|

Michael Derbyshire |

Fogg |

|

Tony Simpson |

Judge |

|

Colin Cunningham |

Usher |

|

David Harris |

Sergeant Snubbins |

|

Brendan Barry |

Sergeant Buzfuz |

|

Peter Bull |

Directed by Peter Coe

Decor: Sean Kenny

Costumes Roger Furse |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

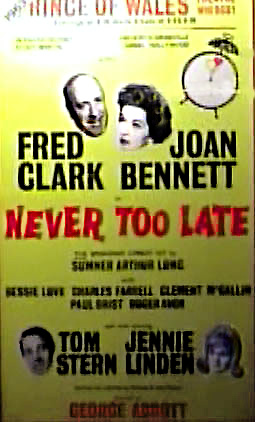

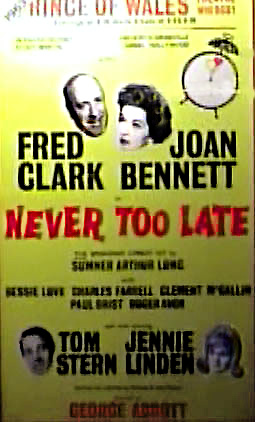

‘NEVER TOO LATE '

In order of Appearance:

|

Grace Kimbrogh |

|

Bessy Love |

Harry Lambert |

|

Fred Clark |

Edith Lambert |

|

Joan Bennett |

Doctor James Kimbrogh |

|

Clement McCallin |

Charley |

|

Tom Stern |

Kate |

|

Jennie Linden |

Mr Foley |

|

Roger Avon |

Mayor Crane |

|

Charles Farrell |

Policeman |

|

Paul Grist

|

Directed by George Abbott

|

| |

| |

|

1964

|

Arthur Lewis, the American producer, director and writer, had arrived back in London in 1963 to run the Shaftesbury Theatre. Arthur had previously worked in this country as the director of ‘Guys and Dolls’ at the Coliseum theatre in 1953. He then returned to America, where he was the associate producer of ‘Can Can’, ‘The Boyfriend’ and ‘Silk Stockings’.

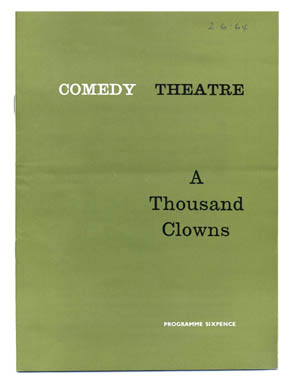

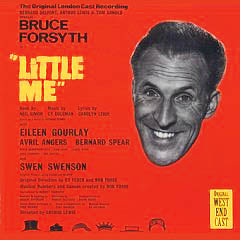

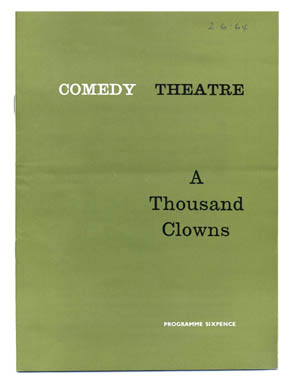

In London, he joined up with Bernie and co-produced with us ‘A Thousand Clowns’, starring James Booth and Roy Kinnear at the Comedy theatre, which opened on June 2nd. Later on this year, we were to co-produce with Tom Arnold and Emile Littler, ‘Little Me’, book by Neil Simon, music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by Caroline Leigh and starring Bruce Forsyth. It opened to rave notices, but it failed to capture the imagination of the British public and although it had a respectable run, it lost money.

During the rehearsal period there was an almighty row between Emile Littler, (who controlled the Cambridge Theatre where we were opening), Bernie, and Tom Arnold. Emile wanted to bar one of the major critics from the theatre, since this particular critic had upset him on a previous occasion. Bernie and Tom argued vehemently that he couldn’t do this, because it might result in a boycott by all the other critics. It got down to the stage of solicitors’ letters, but eventually it was resolved. The critic came and gave us a fair notice.

Emile was rather preoccupied with litigation. He had previously crossed swords with the master, who could out-litigate anybody - Harold Fielding, who, when he presented ‘Half a Sixpence’, starring Tommy Steele at Emile’s theatre the Cambridge, queried some of the expenses Emile charged him with. The lawyers grew fat on the missives which sped to and fro between the two adversaries - the highlight of which was Counsel’s opinion being sought on whether an India rubber constituted part of box office stationery, since Harold contested that he should not have to pay for it. He won, cost Counsel’s opinion £200, cost India Rubber 3 pence, a pyrrhic victory – but that was Harold.

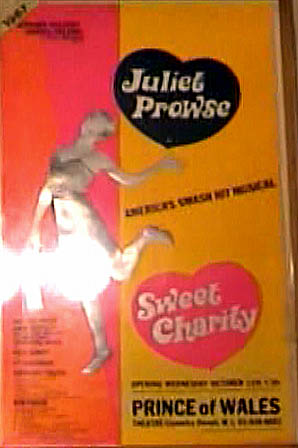

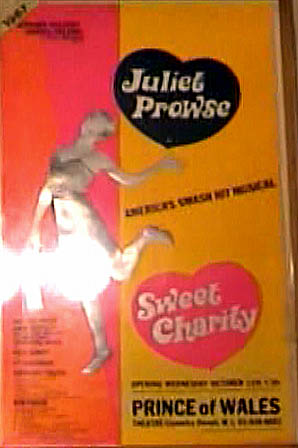

On a later occasion when we were co-producing ‘Sweet Charity’ with him at the Prince of Wales theatre, he saw the property master boiling a kettle on a gas ring to make a cup of tea. ‘Who is paying for that gas – the theatre or the producers?’ he asked; but on that occasion it was decided not to seek Counsel’s opinion.

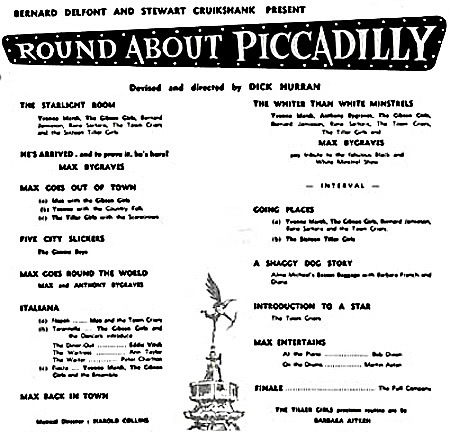

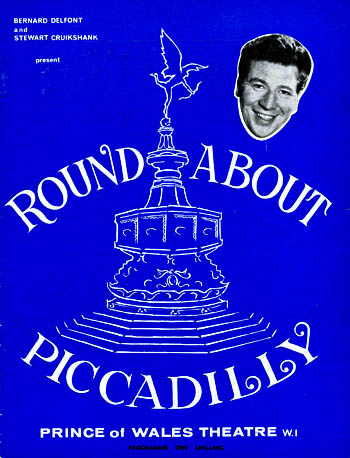

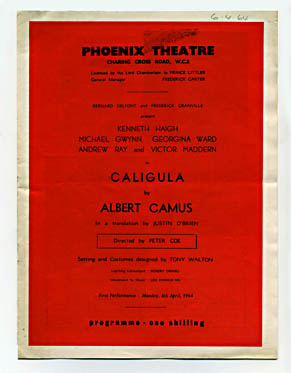

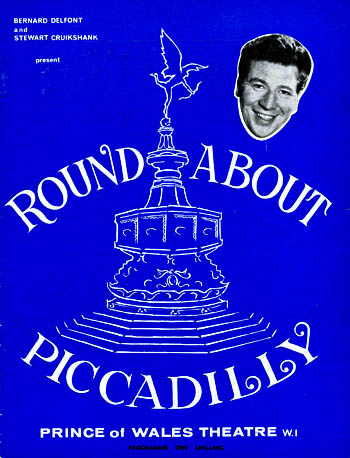

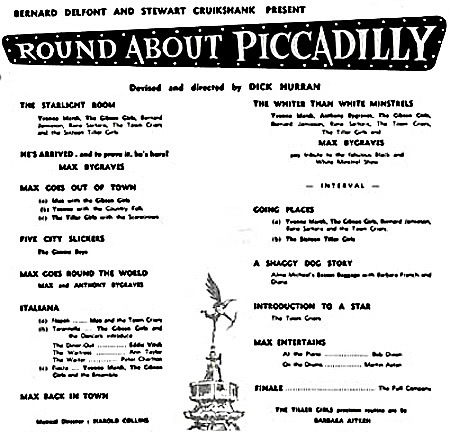

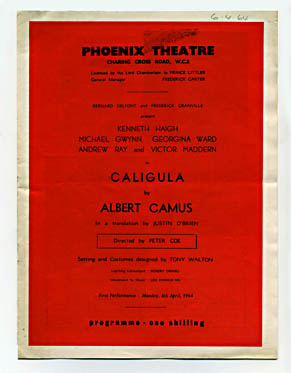

We presented ‘Round About Piccadilly’, starring Max Bygraves, which was running at the Prince of Wales quite successfully. Freddie Granville was still active with Bernie at the Phoenix theatre, co-presenting ‘Caligula’, directed by Peter Coe and starring Kenneth Haigh.

Early this year, Bernie sold his agency to Leslie Grade for £100,000 in cash, and 200,000 shares in the Grade Organisation. This was seen as a family monopoly by some of the press, but it was nonsense, because the brothers were always in strong competition with each other. Nothing much changed; Bernie joined the Board of the Grade Organisation in a non-executive role, and thereafter concentrated on the West End shows and theatres.

Billy Marsh was left to carry on as always, and continued to book all the summer season shows and the headliners for the Talk of the Town. Bernie had been asked by the Cunard Line to book all the entertainment on their ships, and this became my particular province. Booking the artists was easy, but the paperwork - getting them to join the Seamans’ Union, getting special visas for some ports of call, etc., etc., was astronomic. It wasn’t something I enjoyed.

I was still playing a lot of poker. Charles Palmer had decided to branch out from his private games, and opened a poker club called The Sorbonne, in the Cromwell Road opposite the Natural History Museum. He did very well there - and so he should have, since he was taking five per cent out of every pot, which meant that most of the players’ money finished up in his pocket rather quickly. It was such a lucrative operation that some local villains tried to muscle in, by offering him protection. Charles, less than politely declined, saying, ‘I’ll take care of that myself, thank you’. By coincidence, one of these villains disappeared, and rumour had it, that he was helping prop up one of the supports of the Hammersmith flyover.

Apart from the poker, I also had my fair share of cricket. Playing in a match against the Cross Arrows at Lord’s, I was batting at one end and at the other end, was a butch ballet dancer from New Zealand who danced principal roles with the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden.

His name was Brian Ashbridge, and he was to dance a leading role in a new ballet, which was due to open that night at Covent Garden. In those days, helmets for batsmen had not been invented. He received a ball from the quick bowler, which caught the top edge of his bat and smashed him straight in the face, which rather re-arranged his features. We carried him back to the dressing room, and he mumbled, ‘What am I going to do? I’m due on stage in three hour’s time’. ‘Leave it to me’, I said. I phoned up the theatre, and did a ‘Michael Sullivan’, explaining that I was Brian’s doctor; that he had been stricken with a virus and was unable to perform that evening.

I said to Brian, as we loaded him into a taxi to take him home, that the virus was going to have to last at least two weeks if he didn’t want the ballet company to see what state his face was in. I only mention these matters to point out that there was a little more to my life than just show business.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

‘CALIGULA'

by Albert Camus

Translated by Justin O'Brian

In order of Appearance:

|

Octavius |

|

Geoffrey Russell |

Lucius |

|

Norman Pitt |

Old Patrician |

|

Frederick Farley |

Cassius |

|

Rob Inglis |

Trebonius |

|

Tony Caunter |

Helicon |

|

Victor Maddern |

Lepidus |

|

Sean Curry |

Patricius |

|

Murray Scott |

Guards: |

|

Paul Grist

Barry Jackson

Eric Mason |

Cheria |

|

Michael Gwynn |

The Chamberlain |

|

Jeffrey Wickham |

Scipio |

|

Andrew Ray |

Mereia |

|

David Nettheim |

Mucius |

|

Walter Hall |

Caluligua |

|

Kenneth Haigh |

Caesonia |

|

Georgina Ward |

Mucius's Wife |

|

Rosemarie Dunham |

1st Poet |

|

David Nettheim |

2nd Poet |

|

Walter Hall |

3rd Poet |

|

Paul Grist |

4th Poet |

|

Murray Scott |

5th Poet |

|

Sean Curry |

6th Poet |

|

Tony Caunter |

Slaves: |

|

Paul Grist

Barry Jackson |

Directed by Peter Coe

Decor: Tony Walton |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

‘A THOUSAND CLOWNS '

by Herb Gardner

In order of Appearance:

|

Murray Burns |

|

James Booth |

Nick Burns |

|

Chris Barrington |

Albert Amundson |

|

John Cater |

Sandra Markowitz |

|

Andree Melee |

Arnold Burns |

|

Sydney Tafler |

Leo Herman |

|

Roy KInnear |

| |

|

|

Directed by Herbert Hirshman

Decor: George Jenkins |

| |

| |

|

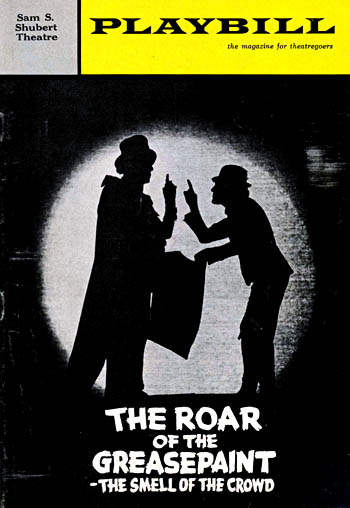

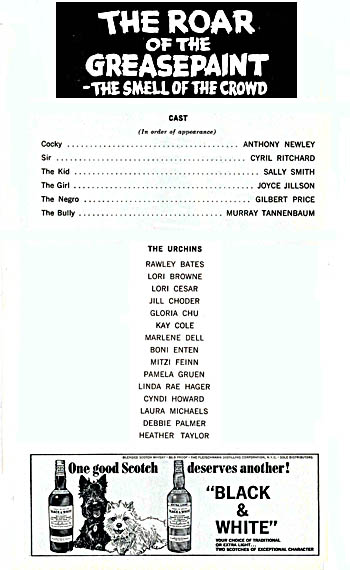

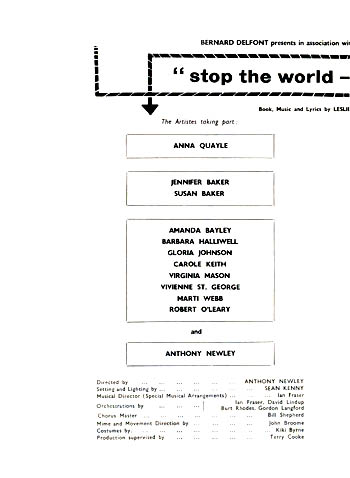

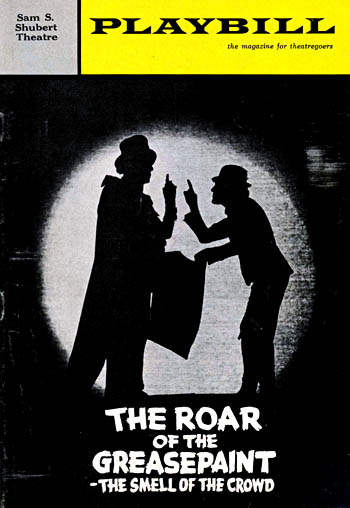

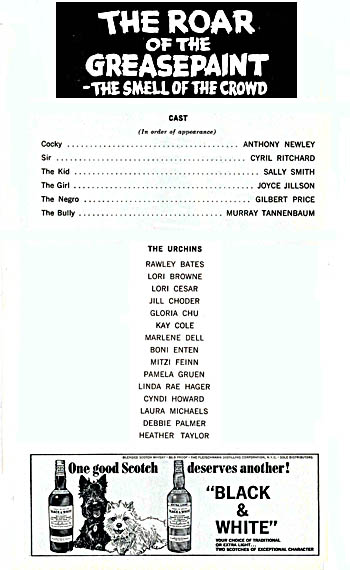

Following the success of ‘Stop the World I Want to Get Off’ in 1961, Bernie was about to present another musical by Tony Newley and Leslie Bricusse, entitled, (after a great deal of debate), ‘The Roar of the Greasepaint the Smell of the Crowd’. Bernie put me in charge of the production, which starred Norman Wisdom with Tony directing, and Gillian Lynne choreographing. Among the cast were two sixteen year old girls, Elaine Paige and Sheila White. I didn’t notice Sheila at the time but twenty years later, I was to marry her.

Rehearsals were rather volatile with Norman and Tony continually falling out. On one occasion, it nearly developed into a fight. Fortunately for Tony, it didn’t, since Norman had been flyweight champion of the Army during the war.

We opened in Nottingham on August 8th and it wasn’t well received. Bernie said that unless it was improved during the five-week tour we had booked, he wasn’t prepared to bring it into London. Leslie and Tony worked very hard during the next four weeks, but no matter what they tried, it appeared to get worse. It had a great score, ‘The Joker is Wild’, ‘On a Wonderful Day Like Today’, but the book was the problem. So Bernie reluctantly closed it in Manchester.

David Merrick (who was once called the abominable showman) asked Bernie if they could co-produce it on Broadway, subject to the fact that Tony starred in it. Bernie agreed, and it went on to become a hit. This cemented Tony as a star in America, and for the next fifteen years he was an enormous attraction on the No. 1 cabaret circuit, particularly in Las Vegas.

Stars at the Talk of the Town this year included Shirley Bassey, Alma Cogan, Bruce Forsyth, Nina and Frederick and a return visit from Lena Horne. On 19th February, it was time for the great Ethel Merman to play a season.

For many years Merman was the First Lady of Broadway. Musicals were written for her. Cole Porter wrote five, including 'Anything Goes'. Also written for her were 'Annie Get Your Gun', 'Call Me Madam' and 'Hello Dolly', which was originally written for her, but she didn't appear in it until the 70s as the last Dolly Levi. What however was considered her finest performance was in 'Gypsy'. She was very briefly, for a matter of weeks, married to Ernest Borgnine.They were both about 60.

There is an apocryphal story that Merman came home one day to find Borgnine with his nose buried in the sports section of a paper and she announced: 'I've just been to see Jack Warner at the film studio and he told me that I had the legs of an 18 year old - the bust of a 25 year old and the face of a 30 year old. Borgnine wearily lifted his eyes from the sports page and asked: 'Did he say anything about your 60 year old c**t? 'No, she replied, 'he didn't mention you at all'.

She was the first artist to appear in this country who used a radio mike. It was her own personal property, and she brought it over from America. Now why Ethel Merman, (whose voice could stop a train), should need a radio mike, was I suppose, for the linking dialogue between her songs. She certainly packed a punch. She made her entrance from the front of house, bursting down the centre gangway, belting out, ‘There’s No Business Like Show Business’. She looked totally unstoppable; it puts me in mind of what Ernest Borgnine was purported to have said when he was married to her. ‘Kissing Ethel Merman is like kissing a Sherman tank’. And that’s what she was like – unstoppable as a tank. What a performer!

The radio mike created more problems than it solved. It was operating on a frequency which was used by taxi cabs, so in the middle of her act, she often got a call asking if she could go somewhere to pick someone up. It didn’t finish there; the police intervened and said it was operating on an illegal wavelength, which was close to the wavelength used by police and ambulance services. They threatened Bernard Delfont with arrest if he didn’t stop it. Fortunately, Bernie had some friends in high places that also happened to be fans of Ethel Merman, so the whole thing was smoothed over. She could certainly have earned a few extra bob during those four weeks, operating a taxi service.

Ethel Merman quotes: - "I can hold a note longer than the Chase National Bank"

"Some things in life aren't even worth regretting. You're better off passing them like a freight train passes a hobo".

Surely this is totally politically incorrect. Hobo should be an itinerant person with few material possessions and no visible means of support. As for the freight train, (since machines are more and more considered to think for themselves), would it not be upset to be considered uncaring.

Will you excuse me for a moment I just have to take my computer for a walk in Richmond park. |

|

|

..................................American Production

|

............... ....American Production cast list

....

|

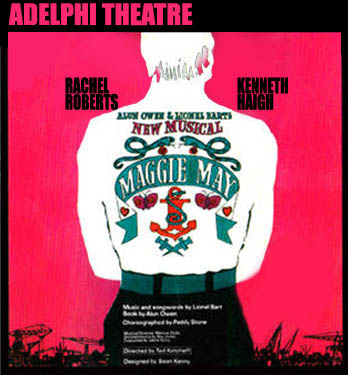

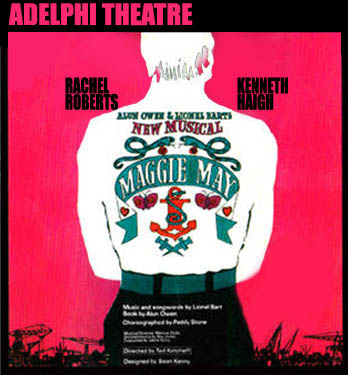

We produced ‘Maggie May’ which opened at the Adelphi Theatre in the Strand on 22nd September 1964, after trying out at the Palace Theatre, Manchester. The music and lyrics were by Lionel Bart, with book by Alun Owen. It was directed by Ted Kotcheff, and choreographed by Paddy Stone. As always, Paddy’s work was great. He even managed to create a dance routine out of the dancers jumping up and down on the same spot. It stopped the show, but years later created lots of problems in the joints of some of the dancers who performed it.

Sean Kenny was the designer. It was a typical ‘Sean’ design; very complex interlocking machinery, all driven by electric motors. I was very nervous of this, and asked him if we could have some manual winches as a back-up. His reply was, ‘Richard, one day they are going to land a man on the moon, and they’re not going to winch him up’.

Rachel Roberts and Kenneth Haigh played the leading roles. Playing a small part ‘The Balladeer’, was the, as yet unknown, Barry Humphries, who opened the show as a one man band, singing a number entitled ‘The Ballad of the Liver Bird’. I can’t remember why, but he left during the run.

Someone else who went on to do quite well for himself was a stagehand, who was in charge of the revolve, which operated all the scene changes. He didn’t always push the right buttons at the right time. On one occasion, he pressed a wrong button and the scenery, with the cast on it, finished up belting out a number facing the back wall. His name was Eddie Shah, and he went on to become a multi-millionaire in the publishing business. Another young hopeful in the chorus was Julia McKenzie, who went on to become a great leading lady.

Rachael Roberts told me during the run, that her friend and my ex-girlfriend Jessica had had a burst pipe in her flat. A plumber came round to fix it and she finished up marrying him.

The show was reasonably well received by the press, and ran for over a year doing steady business, during which time we changed the leading lady twice, Georgia Brown taking over from Rachael Roberts and then Judith Bruce from her; the leading man was also changed twice. Bernie came out of it very well, having pre-sold the film rights to United Artists for a quarter of a million pounds.

Later on I was with Sean having a drink in the actor’s club Gerry’s in Shaftesbury Avenue. I mentioned that having done several shows with him, it would be nice to have an original design as a keepsake. ‘No problem’, he said. He asked Bunny May who was running the club, if he could have one of his saucers. He then produced a Phelp pen, and drew me a striking picture on it which he signed. I took it home with great pride, and put it on the sideboard.

When I returned from the office the next day, it was missing. I asked the lovely lady, Mo Daly, who was the caretaker in the block of flats where I lived, did all my cleaning and generally looked after me like a son, if she had seen it. ‘Oh, don’t worry about that dirty saucer. I’ve washed it up for you’. I didn’t have the heart to tell her.

Some years later, Sean asked to see me in my office. He had been asked to advise on the design of a new theatre in Drury Lane, which was to be on the site of the now derelict Winter Garden, to be called The New London, in which we were to have an interest and administer. He said he would appreciate my advice about various elements, as producer and a man who ran theatres.

After a discussion lasting about three hours, in which I outlined what I considered to be the perfect theatre; one that seated about twelve hundred people, so that it could be intimate enough to present large scale plays as well as musicals, together with plenty of depth and wing space, which would be needed for a reasonably sized musical. And last, but by no means least, the orchestra pit to be large enough to hold twenty-four musicians. He thanked me profusely, and left.

The theatre was finally built in 1973. The front of the stalls and the stage revolved to form a circle. The stage was very shallow; there wasn’t enough wing space. The orchestra pit was a narrow slit, which at a push, could accommodate seven musicians, and the auditorium only seated nine hundred. It was everything I had suggested it shouldn’t be. We struggled for years trying to make it work, and finished up using it mainly for conferences. However, Sean had the last laugh. In 1981, it eventually became the home of ‘Cats’, at one time the longest running musical in the histoy of the West End.

Back at Jermyn Street, I was still in the same office as Billy Marsh, but by now, I had my own desk. I was doing my thing on one side of the room, and he was doing his on the other. I was having some difficult, protracted negotiations with the agent of one of the featured artistes in ‘Maggie May’. This went on for several days, and I noticed that Billy would always pay particular attention when these conversations took place. I discovered some time later, that the artist I had been discussing, was the previous husband of Billy’s wife, Mary. Billy always played his cards so close to his chest – he never told me.

Spike Milligan was appearing in ‘Oblomov’ at the New Lyric Hammersmith. After a week or two of playing it straight, he decided to reinvent the piece, filling it full of ‘Goon’ type comedy. It became a rip roaring success; Michael White came to see me to arrange a transfer to the Comedy theatre, which we were then managing.

The title was changed to ‘Son of Oblomov’ and it opened on 2nd December. Spike was as usual his eccentric self, nobody in the cast knowing what he was likely to do next. On one occasion, just five minutes before the curtain was due to go up on a matinee, he called the Company Manager into his dressing room, to inform him he didn’t wish to do the show. (Being Spike, he didn’t have an understudy). The Company Manager replied, ‘But Spike, you can’t do this at such short notice - most of the audience are already seated, waiting for the performance to begin’. Spike said, ‘Well - invent something. Tell them that I was suddenly taken ill and I’m in intensive care in hospital, but have just managed to phone, to say how dreadfully sorry I am to inconvenience my public. I wouldn’t let them down for the world – but there’s nothing I can do about it’.

The Company Manager made an announcement from the stage conveying Spike’s message - saying they could have their money refunded, or tickets for another performance. As the audience shuffled disconsolately from the theatre, Spike Milligan, with a bucket and leather ,was happily washing his car on the corner in full view of passers-by. I was never quite sure how Michael White managed to deal with the subsequent complaints.

I went to a very special Sunday night concert at the Palladium in November. It was Judy Garland performing with her daughter Liza. I think it was the first time they had ever worked together on stage. For all I know it might have been the only time – but it was a truly magical evening.

It appeared to me that Judy was a little cautious about the vast talents of Liza which she was nurturing. Perhaps she felt she was in danger of being occasionally upstaged. But this was probably only my opinion. Judy was a great star – but I felt she was starting to decline a little. Incidentally what is a star? Well I suppose first of all we have to put them into three categories. Megastars – like The Rolling Stones who played to over 1m people in a concert held on the beach front of Rio de Janeiro – Barbra Streisand who played to an audience of 150,000 in New York in Central Park in 1968 – obviously The Beatles.

THE NEXT 2 PARAS NEED REWRITING

Then we have Superstars who can sell out a concert tour in stadiums seating upwards of 20,000 people, Shirley Bassey, Elton John. Actors who can sell films by the very fact that they are appearing in them. This is usually allied to you know what you are going to get – for instance when Bruce Willis or Arnold Schwarzenegger appear in a film. Is Johnny Depp a Superstar? Because you never know what you are going to get with him – but it’s usually pretty good. Stanley Matthews, the famous footballer was a superstar. When he was playing, it could put 20,000 people on the gate.

Then we have stars who, although they don’t sell tens of thousands of tickets in a one off situation, can help a play or musical playing to capacity for a reasonable length of time.

Incidentally after stars we have what is known as booking names which doesn’t necessarily mean the public will pay to go and see them – but because of their profile in the entertainment business they help to launch the film or find a West End or Broadway theatre for a play or musical.

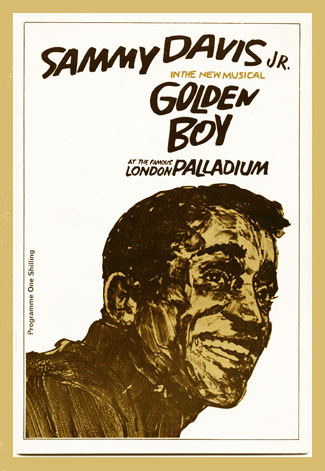

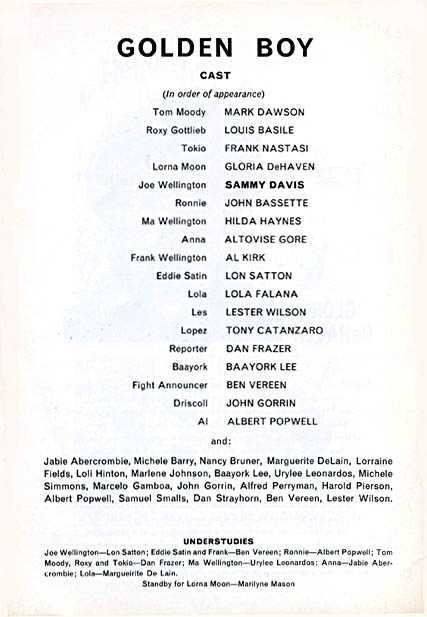

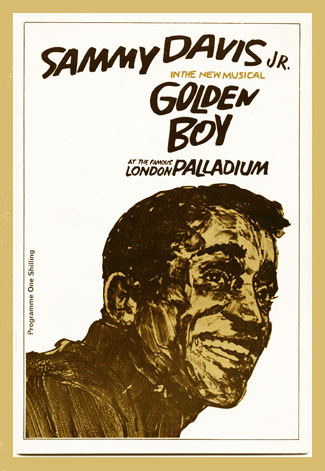

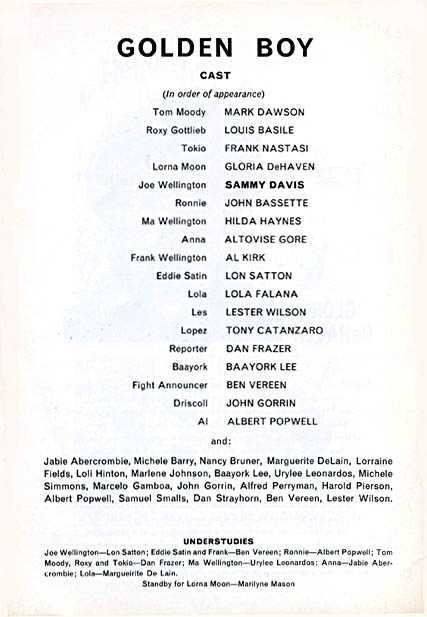

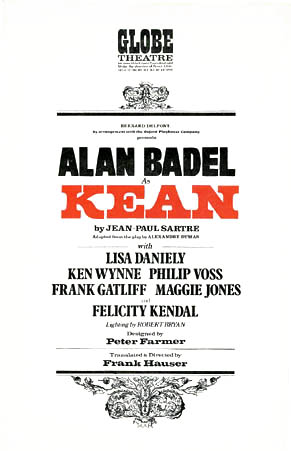

Anyway, whatever category stars are in, is it somebody that sells tickets at the box office? Partially – yes. There are a lot of film actors who sell tickets but I don’t consider them stars. Is it someone who has a great talent? I have seen many performers with great talent – Alan Badel being one. But they are not stars. Is is someone who trades on a reputation of all the things they have done in the past? Is it someone who is unique? Is it someone who when you see them perform makes the short hairs on the back of your neck stand up? Oh yes – that’s definitely part of it. Angela Lansbury did that to me when I saw her performing in Gypsy as did Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl. There are many others but I won't go through the list. Is it someone who is breathtakingly beautiful like Garbo? Not necessarily but the helps. Is it somebody who is multi-talented? Roy Castle certainly was but he wasn’t a star. Vocal talent obviously makes a star. Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand, etc. etc. Voice helps – John Gielgud, Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole, Katherine Hepburn – all had a particular unusual quality but finally it is charisma. I can’t define it – its just there. In my opinion, one of the great stars was Sammy Davis Jnr.

Upon reflection of the above, a film star is probably created because although films are made for distribution to millions of people, in my era when we gazed at the silver screen we were oblivious to everyone else – it was just a highly personal contact between us and the actors in the film and we associated with them. I’m sure every girl wanted to be either Shirley Temple or Judy Garland and the boys wanted to be Tarzan or Robin Hood but as we grew up we decided we couldn’t swing from lampposts or shoot arrows into traffic wardens pretending they were the Sheriff of Nottingham.

We therefore switched our allegiance to actors like Clark Gable and Marlon Brando whilst the girls wanted to be Scarlett O’Hara or Marilyn Monro. The girls then fell in love with the male actors and the boys fell in love with the female actors – or vice versa. This helped to create the film stars.

But the most emotive of the arts which is easily able to arouse feelings of exhilaration, pleasure, nostalgia and sadness is music. So probably the greatest crowd-pulling stars of all are vocalists, but not musicians. Because we can identity with vocalists – 99% of the population are guilty of singing in the bath and thinking (thanks to the acoustic qualities of the bathroom) that they sound like Frank Sinatra or Barbra Streisand. Now it's difficult to play an instrument in the bath – but if Yehudi Menuhin had made a film called ‘Stringing in the Rain’ undoubtedly someone, somewhere, would try and give a soggy version of Handel’s Water Music on the violin under the shower.

The above doesn’t necessarily define what creates a star, but at least it provides an opportunity for my idiosyncratic rambling.

|

|

|

| |

‘MAGGIE MAY '

Book by Alan Owen

Music and Song Words by Lionel Bart

In order of Appearance: |

A Balladeer |

|

Barry Humphries |

Young Priest |

|

Stephen Taylor |

Mrs O'Brian |

|

Janette Gail |

Mrs Casey |

|

Margot Cunningham |

Mother Monica |

|

Charlotte Howard |

Maggie May as a child |

|

margaret Howe |

Sister Mary |

|

Janet Webb |

patrick Casey as a child |

|

Malcolm Collingham |

mrs Nugent |

|

Marie Conmee |

parish Prist |

|

Vernon Rees |

Willie Morgan |

|

Andrew Keir |

Marget Mary Duffy (Maggie May) |

|

Rachael Roberts |

Maureen O'Neill |

|

Diana Quiseeky |

1st Chinese Sailor |

|

Victor Mansi |

2nd Chinese Sailor |

|

Stanley Fleet |

Milkman |

|

Fred Evans |

Children: |

|

Carol Bird

Jaquaeline Lewis

Terry Brooks

Peter Newton |

Old Dooley |

|

Paul Farrell |

Cogger Johnston |

|

Michael Forrest |

Terry Collins |

|

Billy Boyle |

Gene Kirenan |

|

Geoffrey Hughes |

Patrick Casey |

|

Kenneth Haigh |

Stevedore |

|

Joe Sealy |

Crane Driver |

|

Geof L'Cise |

Nora Mulqueen |

|

Marie Conmee |

Ned |

|

Stanley Fleet |

Miss Singleton |

|

Paul Bell |

Police Sergeant |

|

Sean Curry |

The Nocturnes: |

|

David Wilcox

David Foley

David Elias

Francis Sloan

Keith Draper |

Police Inspector |

|

Vernon Rees |

Sergeant/Corporal |

|

Vincent Mansi |

| |

|

|

Directed by Ted Kotcheff

Decor: Sean Kenny

Costumers: Leslie Hurry |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

LIONEL BART QUOTE: "I hated money and had no respect for it. My attitude was to spend it as I got it."

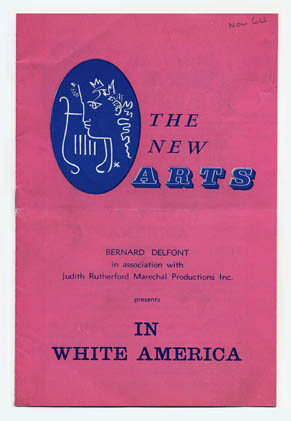

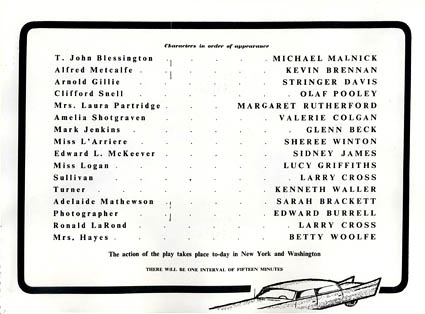

At the Arts Theatre we produced ‘In White America’, directed by Peter Coe. We had thought that it was going to be difficult to cast, since at the time, there were a limited number of black actors in this country; however, it transpired that the actors we found performed magnificently. It was only a short run, but an artistic success, which is all we ever expected it to be.

|

| |

|

|

| |

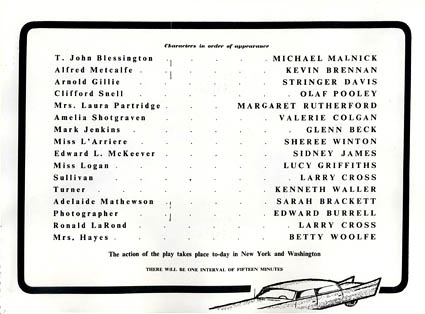

‘IN WHITE AMERICA '

A Documantary Play

By Martin B. Duberman

...

|

Robert Ayres |

|

EARL CAMERON |

Bunny Clarke |

|

GORDON HEATH |

Bessie Lve |

|

NEIL MCCALLUM |

| |

|

|

Narrator:: EDWARD BISHOP

Musician: : fITZROY cOLEMAN |

| |

Directed by PETER COE

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

BRUCE FORSYTH

‘LITTLE ME '

Book by Neil Simon

Music by Cy Coleman

Lyrics Carolyn Leigh

based on the novel by Patrick Dennis

In order of Appearance: |

Noble Eggleston

Mr Pinchley

Val Du Val

Fred Poitrine

Otto Schnitzler

Prince Cherny

Yong Noble |

|

Bruce Forsyth |

MC

Butler |

|

Ted Gilbert |

Patrick Dennis |

|

David Henderson-Tate |

Miss Poitrine |

|

Avril Angers |

Mum Hoggs Father |

|

Bee Duffell |

Belle

Baby Belle |

|

Eileen Gourlay |

George Musgrove

(as a boy)

1st Sailor |

|

James Land |

Cecil |

|

Jamie Fraser |

Daphne |

|

Rosemary Smith |

Lydia |

|

Elizabeth Edmiston |

Lady Eggleston |

|

Enid Lowe |

Bentley

Doctor

Tennis Pro

Preacher |

|

Tim Bamber |

Miss Kepplewhite |

|

Susan Robinson |

Nurse

Woman |

|

Doreen Croft |

Kleeg |

|

Robert Simmons |

Golf Pro |

|

Elwyn Hughes |

Seargeant

1st Steward

Newsboy

|

|

John Howard |

Bernie Buxgrave |

|

Jack Francois |

Benny Buxgrave |

|

Laurie Webb |

Colette |

|

Diane South |

George Musgrove |

|

Swen Swenson |

Announcer

Victor

Soldier |

|

Glenn Willcox |

Red Cross Nurse |

|

Glennis Beresford |

German Soldier

General Schreiber

Pinchley Jnr.

Ship Captain

Assistant Director

Yulmick

Defense Lawyer |

|

Bernard Spear |

2nd Sailor |

|

Michael Tye-Walker |

2nd Steward

Pharaoh |

|

Michael Billington |

Directed by Arhur Lewis

Decor: Robert Randolph

Costumes: Robert Fletcher |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

‘OUR MAN CRICHTON '

Based on the Admirable Crichton by J.M. Barrie

Book and Lyrics by Herbert Kretzmer

Music by David Lee

In order of Appearance:

|

Tweeny

|

|

Millicent Martin |

Crichton |

|

Kenneth More |

Henry, The Earl of Loam |

|

George Benson |

Lady Mary |

|

Patricia Lambert |

Lady Agatha |

|

Dilys Watling |

Lady Catherine |

|

Anna Barry |

The Hon. Ernest Woolley |

|

David Kernan |

Rev. John Treherne |

|

Peter Honri |

Countess of Brocklehurst |

|

Eunice Black |

Lord Brocklehurst |

|

Glyn Worsnip |

Carruthers |

|

Ken Lacey |

Robbins |

|

Jeff Hall |

Kelly |

|

Trevor Willis |

Housekeeper |

|

Peggy Rowan |

Ladies' Maids: |

|

Elinor Heslop

Mary Murphy

Jean Collins |

Dockers: |

|

Dennis Reynolds

David Wheldon-Williams

Hugh Elton |

|

|

Jeff Hall |

1st Officer |

|

Chris Robson |

Directed by Clifford Williams

Decor: Michael Annals

|

| |

|

KENNETH MORE QUOTE: "Oh, Mr Coward, sir - I could never have an affair with you, because you remind me of my father!"

|

|

|

Bernie asked me to move from Billy Marsh to an office next to him, in the Prince of Wales theatre. His feelings were, that he had so much on the cards, it would be better if I were close by. It was goodbye to: Billy, the Cunard Line, (thank God), the agency, and all of the light entertainment, (or so I thought).

‘Round about Piccadilly’ closed in March 1965, and its place was taken by ‘Travelling Light’ which opened on 8th April, starring Michael Crawford, Harry H. Corbett and Julia Foster. This didn’t do very well and subsequently closed after one hundred and forty-eight performances.

Wolf Mankowitz was in the process of producing a new musical, ‘Passion Flower Hotel, adapted from the novel by Rosalind Erskine, book by Wolf Mankowitz, lyrics by Trevor Peacock and music by John Barry. There were no stars as such; just a plethora of young talent, including: Pauline Collins, Francesca Annis, Jane Birkin, Nicky Henson, Bill Kenwright, (later to become an extremely prolific producer), and my friend, Bunny May - a man of diverse talents.

Having read the book, I listened to the music, and told Bernie that although I didn’t think it would set the town alight, I thought it had a fair chance. I went up to see its opening at the Palace Theatre Manchester, prior to coming to London, and was still ambivalent. It wasn’t successful. It opened on 24th August, and closed after one hundred and forty-nine performances. The notices were okay, but not good enough.

Later on that year I went to see a musical at the Adelphi theatre, which opened just before Christmas and was castigated by the press - apart from one good notice in the Sunday Express which ran to about eight lines. It was called ‘Charlie Girl’ and it ran for over four years. I believe it had its finger on the pulse of what the general public wanted; it also had the right cast; Anna Neagle, Joe Brown and Derek Nimmo, and a brilliant marketing strategy from the ace showman, its producer, Harold Fielding.

I had been playing cricket with the Stage Cricket Club for fourteen years, and although I had played reasonably well, scoring many fifties and a few seventies, eighties and nineties, I could never reach the magic figure of one hundred. Then, on July 4th, against the City of London College at Grove Park, I scored 109 not out, and immediately followed it a week later against the Royal Exchange Assurance at East Molesey, with another 100 not out, and they say buses always come along together.

Me, seated 2nd from right ready to open the batting -

my pads were not as clean as they should have been

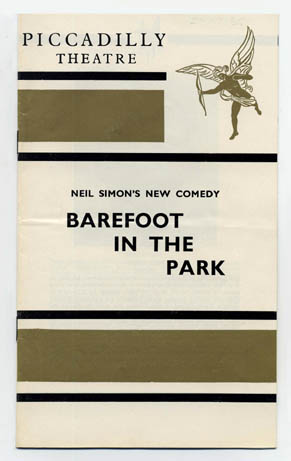

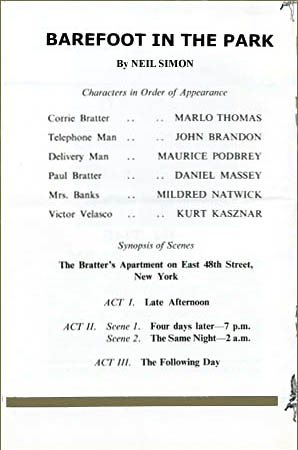

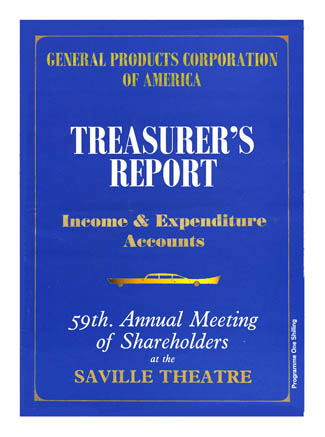

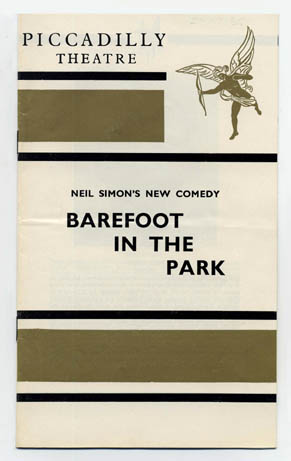

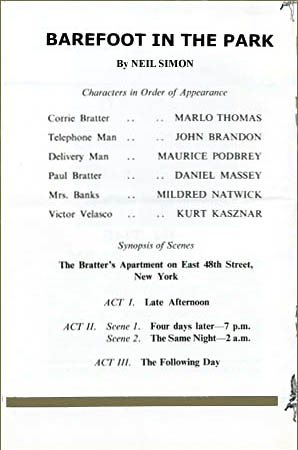

Earlier in the year, we produced ‘The Solid Gold Cadillac’ with Margaret Rutherford and Sidney James, which opened on 4th May and was not a success – nor was Neil Simons’ ‘Barefoot In the Park’, which we opened on 24th November at the Piccadilly theatre. It starred Mildred Natwick, Daniel Massey and Marlow Thomas. Although a big hit on stage in America, and later on a film – as I wrote earlier, the Neil Simon magic just didn’t fully work in London.

|

|

|

|

MARGARET RUTHERFORD QUOTE: "You never have a comedian who hasn't got a very deep strain of sadness within him or her. One thing is incidental on the other. Every great clown has been very near to tragedy."

|

|

|

|

NEIL SIMON QUOTE: "New York is not Mecca. It just smells like it."

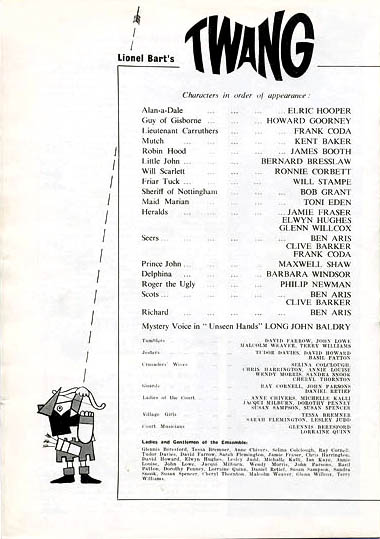

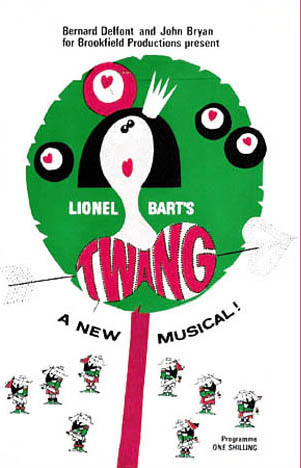

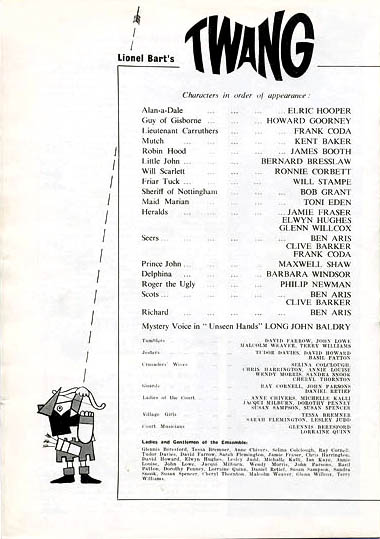

Our failures during this year might have been viewed as minor shipwrecks, because looming up at us, was the Titanic of all musicals – ‘Twang’.

Lionel Bart was on a roll. He started in 1959 at the Theatre Royal Stratford East, working with Joan Littlewood, where he wrote ‘Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be’ which transferred to the Garrick, and ran for two years. Then, ‘Lock up your Daughters’ (lyrics), ‘Oliver’, ‘Blitz’ and ‘Maggie May’. Most of what he touched turned to gold. When he approached us to present his new musical ‘Twang, we jumped at the chance. This was to be produced in association with John Bryan, a film producer, who was backed by Universal Films.

The creative team was Joan Littlewood, (the Queen of improvisation), to direct, Oliver Messel the world-renowned painter, architect, designer and who was responsible for the sets and costumes. Paddy Stone was the choreographer, (he was probably the finest in Europe, and was among the top six in the world)

Paddy had a very short fuse, many times stopping just short of physically assaulting his dancers. He did actually throw a chair at one during the subsequent rehearsals. My theory about Paddy’s frustration was, that he was full of brilliant and inventive ideas, and the dancers, with one or two notable exceptions, just weren’t supremely talented enough to execute them. He was like a painter, who was capable of great art, but found he didn’t have all the necessary colours in his palette. This team, together with Lionel Bart, was either going to be dynamite or oil and water.

James Booth, Barbara Windsor, Bernard Bresslaw and an up-and-coming Ronnie Corbett, were the stars. The rest of the cast, numbering about forty-five, were made up of actors, dancers, singers, tumblers and acrobats. The show took some time to set up. The first inkling of a stormy passage ahead, came when Lionel, who we had been pestering for months to give us a script, suddenly appeared triumphantly, waving seven pages. ‘Where’s the rest of it?’ we asked. ‘Oh, don’t bother about that. Joan is brilliant at improvisation. She’ll just make it up as we go along’, Lionel replied.

The opening date hadn’t been set yet, and we needed to establish the date of the first rehearsal. In those days, a musical would usually rehearse for four, or at the most five weeks. ‘Since you’re making it up as you go along, will five weeks be enough rehearsal time?’ I asked Lionel. ‘Oh no, we need three or four months’, he replied.

After I recovered my composure, I explained that this was out of the question, since, after four weeks of rehearsal pay, the artists all had to be paid full salary. Lionel suggested to me that we wouldn’t officially rehearse; we would just invite all the principal performers to a three or four month party at his large house, which was a converted monastery he had just bought in Fulham, and there they could make it all up with Joan. Not having a lot of choice, I told him we would go along with it, if the artists agreed. Since they were all part of Joan’s company (‘my nuts’), as she called them, from Stratford East, they did.

Instead of getting the script right, Lionel seemed to be more interested in what the front of house sign should look like. He spent a great deal of time discussing it with me, saying he wanted a big neon lit target on the front of the Shaftesbury theatre with neon lit arrows being fired into it from across the road. It took a great deal of time and effort on my part to explain to him that regardless of the wonders of modern invention, this was not a practical proposition. Eventually he reluctantly gave way.

The party for the principals commenced, and arrangements were made for the rest of the company to start rehearsing in two months time. Timothy Burrill, who is today a successful film producer, was assistant to our co-producer, John Bryan. Tim used to pop in from time to time to see how rehearsals were going, and several times found Joan trying to work him into a scene, instead of having him just watching. Joan liked him. But because he was from films, not theatre, she used to say to me, ‘He’s not like you - he doesn’t know how to make cakes’. At first I was puzzled, but then I realised she was alluding to ‘theatrical cakes’. Anyway, Tim was a great guy to work with, and although he couldn’t make theatrical cakes, he could certainly make films.

I paid very few visits to the improvisations at Lionel’s, on the basis that, until they had sorted themselves out, there was nothing I could do. On one of the occasions I did attend, Joan was improvising a scene in Sherwood Forest, when one of the principle actors, (I can’t remember which one), asked Joan if he might be excused to go to the loo. She agreed, and he was away for about five minutes. When he returned, he asked Joan whereabouts he should be standing in the scene. Joan told him not to bother, as she had written him out of the scene in his absence. His response was ‘Christ Joan! I only went to take a piss and you’ve written me out of the scene. Thank God I didn’t go for a crap - otherwise you would have written me out of the musical!’

After two months of improvisation at Lionel’s house, without any appreciable improvement in the script, we commenced rehearsals in earnest with the thirty-five other members of the cast; singers, dancers, acrobats etc.

The rehearsals were held in a complex in north London, which had a very large hall and several large rooms; so the dancers would be in the hall with Paddy Stone, the singers in another room with the vocal coach, and the principals split up into one or two rooms as required. Paddy was working well with his dancers, and the singers were making progress, but the script still lacked cohesion and direction.

Oliver Messel, the designer, had by now started to panic. He didn’t know what sets he was supposed to be designing. Joan had told him not to worry - the shape of show would soon be fixed. Oliver patiently explained that first of all he had to know what all the scenes were; then he had to design them; then they had to be approved, and then, they first of all had to be built, and then painted.

I pointed out to Joan that the time scale for this, for a major musical, even if everyone worked flat out, was five or six weeks. ‘Well in that case’, said Joan, ‘since Oliver knows we need at least a forest and a castle, let him design those, then he can do whatever he wants with the rest of the sets, and I’ll improvise the book around them’.

Since there was no alterative, I conveyed this to Oliver, and between us we worked out what the other scenes might be; village green, banqueting hall, drawbridge, Maid Marion’s bedroom, battlements of the castle etc, etc. Slightly mollified, this he proceeded to do.

We were now fast approaching our opening date, which was to take place at the Palace Theatre, Manchester. The book was still in a mess, and tempers were becoming increasingly frayed. Paddy had choreographed one scene in the forest, where the acrobats were doing cartwheels and turning somersaults; dancers were swinging from trees and generally leaping about.

The costumes for the dancers and acrobats, which Oliver had designed, arrived from Bermans, the costumiers, and although they looked magnificent, they weighed about fourteen pounds each. The acrobats and dancers could barely move in them - let alone perform Paddy’s routine. Paddy had a fit, and it was back to the drawing board with the costumes.

About a week before we were due to open in Manchester, we were rehearsing in the Shaftesbury Theatre, when suddenly, I spotted Harvey Orkin in the stalls; I had played poker with him a few times. Harvey was a theatrical agent from New York, and well-known as a writer for magazines and TV. He had won an Emmy for his contribution to the ‘Sergeant Bilko’ series, and had become a TV celebrity, through appearing in various British. TV shows. ‘What are you doing here Harvey?’ I asked. ‘I’m collaborating with Lionel on the book’, he said. ‘You weren’t yesterday’, I replied. ‘Well, I won part of the show in a poker game with Lionel last night, and thought I’d better come and see if I can help protect my investment’.

We moved to Manchester and staggered through the dress rehearsals. It was still chaos. Bernie and John Bryan had arrived for the first night to join Timothy Burrill and me. When the curtain went up, the four of us were sitting in the centre aisle seats of row F in the stalls. Bernie was on the gangway, with John Bryan next to him, then Tim Burrill and me.

After the musical had lurched its way through the first twenty-five minutes, Bernie rose from his seat and said, ‘I’m going to the bar’. Ten minutes later, John Bryan joined him. We then reached a moment in the plot where Barbara Windsor had to deliver the sort of line that everyone in show business dreads, when a show is not going well. ‘I don’t know what’s going on here’, said Barbara. ‘Neither do we’, came a loud voice from the stalls. Barbara stepped forward to the footlights, and addressed the audience. ‘I’m awfully sorry that it’s a bit of a mess, but we are working on it, and I’m sure we’ll get it right. Now back to the plot’. At this moment I turned to Tim Burrill, and found that he had left as well. I, poor fool, stayed on to the bitter - and I do mean bitter end.

Bernie informed me that he was going back to London the next day, and he would leave me to sort it out.( Thanks Bernie )He asked me to phone him each day to give him a full report.

After a couple of days without any improvement, Joan suddenly vanished, and although we were informed on good authority, she was still in Manchester, no-one could find her. In the meantime, every day we were besieged by the press, who were waiting for the company at the stage door. In the morning when we came in to rehearse, there were between fifteen and twenty reporters. They had smelt blood; they thought this was going to be the biggest disaster in theatrical history - they were right. Every day, there were stories on the front pages of the national press, recounting some new piece of disaster they’d sniffed out.

When Joan disappeared, I took it upon myself to call the entire company onstage, to tell them she had vanished, and delivered a pep talk, saying that we would sort it out, but in the meantime, we should all pull together, and we would somehow make it work. I also asked them not to tell the press. It was headlines the next day.

That evening, becoming aware that Joan might not be reappearing, I called a meeting at midnight, with the production team and Paddy Stone. I didn’t invite Lionel, because I knew what the outcome would be.