NT BOARD AND EXECUTIVES - LATE 1980S

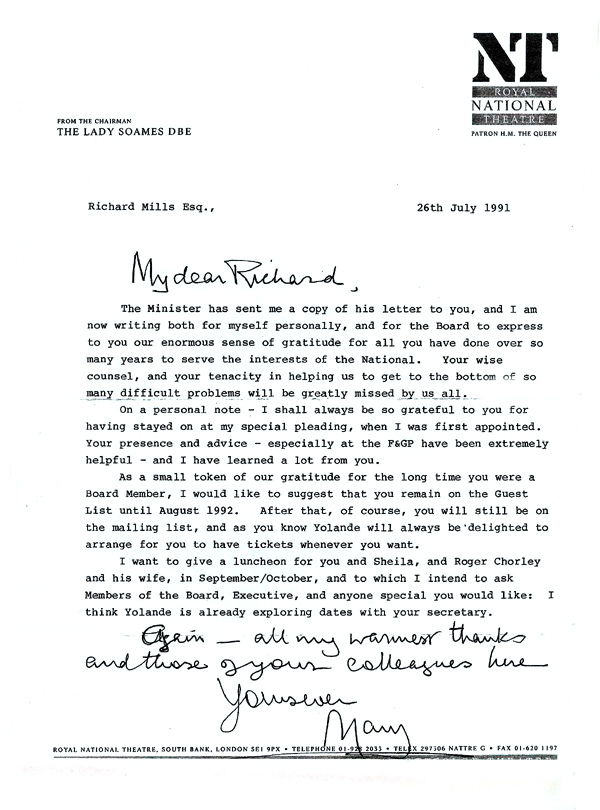

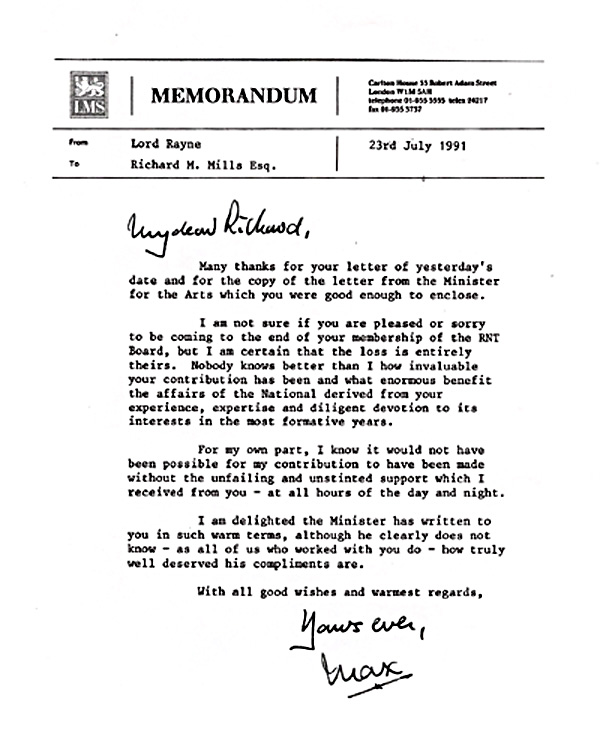

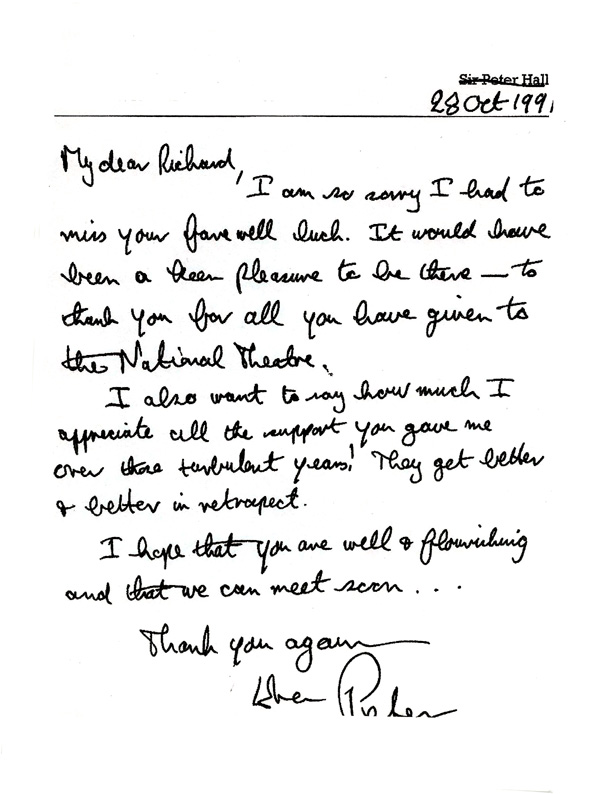

Seated from right to left: me, Lord Chorley, Lord Mishcon, Sonia Melchett, Lady Soames, (daughter of Winston Churchill)

Lord Rayne, Lady Plowden, Lois Sieff, Yolande Bird, Sir Derek Mitchell. Standing right to left: Douglas Gosling, Ronald Baird,

Sir Peter Parker, David Aukin, Sir Richard Eyre, Sir Peter Hall, Timothy Burrill, John Whitney, Rafe Clutton

MY VIDEO RECORDING OF THE NT's TRIBUTE TO LORD RAYNE

Part I - INTRODUCTION AND RECEPTION

Press arrow to start

To exit - click anywhere on navigation bar

Part II TRIBUTE TO LORD RAYNE

(Includes speeches by Lord Goodman, Lord Rayne, Sir Peter Hall, Sir Richard Eyre and John Mortimer)

Rather than wait until all theatres were finished, it was decided that each theatre was to be used as it became available. The Lyttleton opened first in March, the Olivier, in October and the Cottesloe, in March 1977, with Ken Campbell’s and Chris Langham’s production of ‘Illuminatus’, an eight and a half hour long piece from the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool. (So we did open the theatre to outsiders). At my first Board meeting, among the board of heavyweights which Lord Rayne had gathered about him were; Harold Hobson, Sir Ronald Leach, the eminent lawyer Lord Mishcon, (who early on his career, was the solicitor for Ruth Ellis, who was the last woman to be hanged; he was Shadow Lord Chancellor in 1990-1992, but subsequently probably became best known for his role in the negotiations over Diana’s divorce from Prince Charles), Yvonne Mitchell, John Mortimer, Lord O’Brian, Lady Plowden and Consultant to the Board, Lord Olivier. I felt a little overwhelmed in the presence of all these eminent people from the establishment, but took comfort from the fact that I was the only one with knowledge of the nuts and bolts of theatre, with the exception of course, of John Mortimer and Yvonne Mitchell, who certainly exceeded my knowledge on the creative side. I was welcomed with open arms by Lord Rayne, the Chairman, who became a very good friend. On the agenda of the Board, was the question of how to pay adequate tribute to Lord Olivier, (who was not present), for his years of devotion to the cause of creating the National Theatre. There was a feeling of friction between Olivier and Peter Hall, since Olivier was not yet happy to be sidelined, and, if he had been consulted, his choice of a successor might have been someone other than Peter. In the early 60s, Olivier and Lord Goodman had suggested an amalgamation of the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre, the idea I believe was first floated by Laurence Olivier, since he didn’t fancy the competition. This idea was rejected by Peter Hall and the RSC. When the National Theatre opened in at the Old Vic in 1963, more pressure was put on the RSC to get out of London. Years later in the 70s, the idea of an amalgamation was again floated. This time it was supported by Peter Hall; (sometime later, Peter regretted having the idea, thinking it was a mistake on his part to even consider it). Olivier did not support it; he now saw it as a Trojan horse. There was always a certain amount of envy towards the National Theatre, from the rest of the subsidised theatre. A letter was published in The Times in 1974, signed by fourteen directors from the subsidised sector, expressing concern that the National Theatre was going to take most of the money available from the Arts Council, and not only that, drain away a great deal of the talent. Paradoxically enough, one of the signatories to this letter was Richard Eyre, who subsequently, became director of the National Theatre. Years earlier in 1971, when Sir Max Rayne, (later to be Lord Rayne), took over as Chairman of the National Theatre, the opening date of the National Theatre building was to be in 1973. Owing to various building problems, this was pushed back to 1974. There are conflicting reports on how Peter Hall came to be Director of the National Theatre. One, is that according to Laurence Olivier, in March 1972, Max Rayne had a meeting with him, giving him six months formal notice terminating his Directorship and informing him, that his place would be taken by Peter Hall. Olivier was stunned by this; although he had intimated that he was ready to retire, he neither expected such an abrupt dismissal, nor could he understand why, without consultation with him, Peter Hall had been elected. He assumed that discussions would have taken place with him, about his gradual withdrawal from the National Theatre, and his handing over to his successor. He also felt that he should have been consulted about his successor, or even left to appoint him; his preferred choice might have been Michael Blakemore. However, history tells us that he accepted the situation, and that he agreed to be a co-director with Peter Hall, for the last six months of his tenure. This was an eminently sensible compromise, since the future programme of the National, had to be prepared, and it wouldn’t have made sense for Olivier to prepare a programme which Peter Hall wasn’t happy with. They worked amicably together for the six months, then, Peter took over. He inherited a major problem, because the opening of the new building had to be put back yet again to 1975. It wasn’t finished in 1975, or indeed in 1976. 1976 Although the builders were still swarming all over the building ,Peter Hall decided to bite the bullet, and move into the uncompleted Olivier and then open each one of the other theatres independently, as soon as they were nearly finished. His logic was, that if he waited until the building was totally completed, he might not move in until 1978. The Lyttleton was the first theatre to open on 16th March 1976, with Albert Finney’s ‘Hamlet’, the uncut version, directed by Peter Hall. I joined the Board shortly after, and the first trauma I was party to was, that ‘Tamberlaine the Great’ starring Albert Finney, was due to open shortly after in the Olivier; but the machinery didn’t work, nor did the flying system. In order to give the contractors and technicians a chance to rectify this, Peter Hall switched the rehearsals outside, onto the terraces of the National Theatre. The public watched these rehearsals free of charge; they were enthralled. There was a further problem; the stagehands refused to work in the Olivier theatre whilst being on call to work in the Lyttelton. Part of the hidden agenda was, that vast amounts of overtime had been earned by the stagehands at the Old Vic, since each time there was a change of show, there had to be a breakdownof the current production, a get out and then a get in and fit up of the next show; a lot of the time was spent loading and unloading lorries. They also saw the mechanisation of the National, as a way of reducing manning. It was true that modern machinery would mean that less manual labour was required for certain jobs, but on the other side of the coin, at least three times as much work was being done in the new building, thus, there were no job losses. We took this dispute to ACAS, who found in our favour and the stagehands were ordered to return to work. The stagehands refused to accept the ACAS ruling, and a few days later, they all left the building on an unofficial strike. The upshot of this was that the unions disowned them, and suspended their membership. The problems escalated with the unions, but we, on the Board, completely backed Peter Hall and voted, that if necessary, we would bring in casual labour to run the theatres. Finally, a compromise was reached with which the Board agreed,(although Peter Stevens, Peter’s General Administrator and right hand man ), was very much against it. On top of all these problems, Albert Finney contracted bronchitis. However, he made a miraculous recovery; the four and a half hour long play opened on schedule, and was a great success. All the critics were in favour of it, apart from The Sunday Times. Thus, the Olivier Theatre was launched successfully. It was around this time, that Max invited the new Board members, Lady Plowden, Yvonne Mitchell, Harold Hobson, Hugh Jenkins, Rafe Clutton and me, to the Connaught for lunch, to meet Peter Hall, Peter Stevens and each other. On October 25th the building was officially opened by the Queen. The main royal party, headed by The Queen, the Board etc., saw the production of ‘Il Campiello’ in the Olivier Theatre. It was a disaster - preceded by an even worse disaster, of a specially written trumpet version of the National Anthem, played by the trumpeters of the Household Cavalry. It sounded horrible. The only success of the evening was the welcoming speech by Laurence Olivier, who naturally received a standing ovation. The second royal party, headed by Princess Margaret, saw ‘Jumpers’ in the Lyttleton Theatre. In December, a special Board meeting was convened in the evening, to make a special presentation to Laurence Olivier of a crystal bowl. It was a very stilted, uncomfortable gathering; nobody quite sure what to say to Olivier; I don’t think Olivier and Peter Hall were too sure of what they should be saying to each other, in the circumstances. At a Board meeting, some concern was expressed about Peter Hall’s choice of plays for the National. One member of the Board pressed very strongly for a committee of play readers to be set up, which would then recommend to Peter, what the programme should be. This was given very short shrift by the Board. My own feeling was, that if Peter Hall whom we’d entrusted with the gargantuan task of running the National wasn’t able to come up with a successful programme, then a committee certainly couldn’t do it. Max Rayne was never early for Board meetings; he was never even on time; he nearly always late. It became a standing joke among us, all sitting round waiting to start the Board meeting. On occasions, we would even have a sweepstake on how many minutes late he would be. 1977 Later at Board meetings, we started to get the first of many mutterings about Peter’s absences at Glynbourne, to direct operas, the first one being ‘Don Giovanni’. My personal opinion was, that it acted as a refresher for him to escape the constant pressures at the National. Additionally, it kept him happy, by giving him the opportunity to earn some money, since we were paying him very much below what he could have earned in the commercial theatre, and, he had a large family to support. It transpired, that during his tenure at the National Theatre Peter, directed a grand total of twelve operas. It would be only fair to say, that Peter directed these operas instead of taking holidays. Working far below usual salaries, also applied to some of the actors who were based on a four structure pay system. The ones at the bottom being on or around the Equity minimum; the scale gradually increasing, until we got to the top end of the scale, where certain leading actors received what was known as the ‘Knights Top’ - about £400 per week, plus performance money. This was for the really big stars, such as Richardson, Gielgud, Schofield, Finney etc; but the ‘Knights Top’, was probably only about an eighth of what they could earn in the commercial theatre. Of course, there were compensations for them; they had a choice of plum parts, and since a repertory system existed, they usually only played three or four performances a week. There were no such restrictions on the technicians etc; they were paid a reasonable commercial wage. Peter Hall of course, was not on three or four performances a week – he was saddled with the problems of the National seven days a week. At subsequent Board and Finance and General Purposes meetings, I never ceased to wonder, how, in spite of the nightmares of running the National, how calm and composed Peter always seemed to be. I am sure this was just a façade, and that underneath there was a raging turmoil of emotions. He later wrote he’d wake up some mornings and wish that somebody would tell him the National Theatre had burnt down. In any event, by his brilliant use of smoke and mirrors, he ran rings around the Board. However we were not stupid; it suited us to allow him most of the time to do so, based upon the fact that he was performing a gargantuan task, in setting up and running the National Theatre. If we had chosen to meet him head on, it would certainly have meant replacing him at this critical stage in the National Theatre’s development, and with whom? Six months after we opened, there was yet another blow-up with the unions. This was because after all the appropriate warnings, we fired a plumber. Unfortunately, he also happened to be a shop steward. In spite of John Wilson, NATKE’s General Secretary, being on our side,part of the work force came out on an unofficial strike action, staying out for several days, causing the loss of several performances. Peter Hall, along with John Wilson, asked to have a meeting with Len Murray, Chairman of the TUC, which had the effect of resolving the situation. Lord Olivier, who was still the Consultant, wrote to Max Rayne, saying he was fed up with being asked what was happening at the National Theatre and since he wasn’t being kept in the picture by Peter Hall and the Board, he was tendering his resignation. We on the Board had all seen this coming for some time, because we felt that Olivier wasn’t particularly happy with the choice of Peter Hall as Director, nor, was he happy to be side streamed when he was; I’m not sure how he felt about Peter being awarded a knighthood shortly after. Some said, after all he had been through, Peter should have been made a Lord. At a Board meeting later in the year, it was pointed out we’d lost half a million pounds since April. Peter Hall answered this with the fact that it cost one million pounds a year just to run the building, without putting a single production on stage. Also of course, there was the lack of revenue arising from cancelled performances. The Board was getting exceedingly nervous, about the fact that if nobody was going to throw us a lifeline, we might have to close down. If a lifeline was to be thrown, whose responsibility was it; the Department of Education and Science who paid for the building or The Arts Council, who paid for the running of the building and its artistic content, now it was complete? I expressed myself forcibly at the meeting, that there was a possibility, that as Board members, we could be accused of insolvent trading, and, possibly be held responsible. I was reassured by Max and various other political and financial wizards on the Board, that this was extremely unlikely, since we had after all, been made members of the Board by the government, and that it was the duty of the government to provide adequate funding for the running of the building be it through the Arts Council or any other source. I thought to myself, if the experts are not worried - why should I be? Trying to come to terms with the finances of the National Theatre was like to trying to peel away the layers of an onion. Each department considered itself its own fiefdom, and although each department had its own budget, it was very difficult to assess what portion of that budget had been spent on any particular production. Hence, it was virtually impossible to pin down the production costs exactly, of each individual show. Anyone who tried to peel this particular onion was doomed to failure. All that one could come up with were approximate costs. I felt tempted on occasions to get involved in trying to ascertain the exact costs of the productions. Fortunately, I resisted the temptation since it would have been a job which entailed working twelve hours a day, seven days a week with no guarantee of success. In trying to come to terms with our deficit, various proposals were made for cuts of up to £1m from the forthcoming programme, but these were not cuts in the administration and the running of the building itself, but in the plays, which then would have had an adverse effect on box office receipts. Peter Hall was concerned, that in that event, the current administration would have to resign en masse; the theatre would have to be closed down and handed back to the contractors, who would then finish the outstanding work, and in a year or two a new administrative team would be appointed, who would re-open the theatre, and start all over again. Late in the year, we were given special grants to help with the costs. 1978 We seemed to be under constant fire from the press. In March, The Evening News had a front page banner headline shouting “A National Disaster”. Everybody seemed to be sniping at us. If Peter Hall presents the classics - they say we should be presenting new writing. If we do new writing - the critics say we should leave this to the commercial theatre. We are also castigated, for spending too much money on sets, costumes and scenery. Whilst part of me agreed that we could have been seen as being too lavish, the other part of me said, if we have a National Theatre, this should be the jewel in the crown of British theatre, providing the very best of everything. After all, we don’t question the costs of the Trooping of the Colour, the National Gallery, or the British Museum. It was about this time we were starting to be pressed to go out in the market place to find public subsidy. This seemed to me to be contrary to what the National Theatre was all about. It was created by the government, and should be paid for by the government. We shouldn’t have to wander around with begging bowls, scraping up money to do the job we were appointed by the government to do in the first place. Sponsorship was to infiltrate the National Theatre gradually over the next few years. When I first joined the National, there was no sponsorship. When I left in 1991, there was a total annual sponsorship of £0.5m from corporate sponsors, who were categorised as platinum, gold, silver and bronze. The platinum paid £10,000 plus VAT per year, gold £7,000, silver £4,000 and bronze £2,000. Additionally, there was sponsorship for individual productions, touring, platform events, special events and special entertainment evenings, totalling a combined sponsorship in the order of £1.5m. This of course, covered things which were supposed to have been paid for by the government, who had put us there in the first place. The £1.5m of course, eroded the grant we received from the government. Some of the national papers even reported, that the guide on one of the Thames pleasure boats, which passed the National Theatre two or three times a day, was announcing through a loud-hailer: ‘That’s the National Theatre – a monstrosity, run by a pig called Peter Hall’. Generally morale has not been good, and it has not been helped by the fact that there have been a large number of thefts in the theatre, together with rumours, regarding backstage drug pushing. The Board, in order to show its solidarity to Peter, asked him if he would like a three year extension on his contract, which only had another two years to run; he was happy to agree. To ease part of the load on Peter, Michael Rudman was appointed to run the Lyttleton. He was a very good choice, not only creative, but very level headed. On many occasions, he accompanied Peter Hall to Board meetings, where he created a very favourable impression. Morahan and Bryden were appointed to run the Olivier. Later on in the year, Peter Stephens left to join the Schubert organisation in New York. His replacement was to be Michael Elliott. 1979 My dear friend, Yvonne Mitchell died during this year; a sad loss to the National Theatre and to the theatre in general. The problems with the unions continued. They were still refusing our offer, with staff walking out unofficially – but then this was true all over the country. The union members seemed to have gone mad. But soon, Margaret Thatcher was to make the point that the government was running the country – not the unions. At a Board meeting, it was agreed that if there was any unofficial action from NATKE members, we would support Peter in closing the theatres down for a while. The government White Paper said that everybody should stay within 5% limits, but these limits are being breached by among others, with Covent Garden offering 8%. Our stage staff refused to accept the increase we offered, and first of all went on a work to rule, and go slow. Then, in spite of the union leader, John Wilson, urging them against it, they ignored him, walked out of the theatre and began an unofficial strike. We were forced to sack unofficial strikers. In answer to the Board’s question of could there be a compromise, Peter and Michael Elliott, (who had now been appointed in place of Peter Stevens), categorically said ‘No’. Now, we never knew when performances were going to be disrupted and to counter, we sometimes gave performances without scenery and props. Eventually, a compromise was suggested. All the people we had dismissed were offered two choices: 1) they would be reinstated if they signed an undertaking that they were in breach of contract or, 2) they could go to arbitration, and all parties would abide by the decision. How Peter Hall could apply his mind to creative thinking, in the middle of all this anarchy was a miracle. Most people would have cracked under the strain. However, the end was in sight. The industrial action was soon over; the estimated cost of the disruption was in excess of £200,000. ‘Bedroom Farce’ had been an enormous success in the repertoire, but it was due to make way for other plays. I pushed very strongly at a Board meeting, that the National Theatre should capitalise on its own success, and instead of farming it out to an independent producer, the NT should present it in the West End itself. I offered the Prince of Wales theatre, on a very reasonable four wall deal. Theatre deals were at the time based on either a sharing deal, whereby the theatre paid all the expenses to do with the theatre, - i.e. heat, light, cost of all staff, both front of house and backstage, and in return, received an amount of between 30% and 40% of the gross box office receipts; or a four wall deal, in which the theatre provided just the building and front of house staff, the tenant paying for everything else, – i.e. heat, light, stage hands, etc., etc. On this basis, the theatre would receive a guaranteed sum known as ‘the rent’, against a percentage, which could vary between 10% and 20% of the gross box office receipts. Sometimes, the percentage would kick in only after production costs had been recouped, or, if it already existed, it could be increased slightly. There were various permutations on this, but today, four wall deals are the norm. The Board agreed to transfer on a four wall deal. Although ‘Bedroom Farce’ started off very successfully at the Prince of Wales, halfway through the run it started to run out of steam, and although I dramatically reduced my rental terms, the play, because of its heavy transfer and running costs, finished up in deficit. There were a lot of red faces around the boardroom table, mine in particular, since the National Theatre was not created to take commercial gambles. In order to avoid any flack, Max Rayne picked up the deficit personally. Never again was the National tempted to run any West End commercial risks. Everything was always leased out to commercial managements. Subsidised theatre in general feeds the West End, which in turn, feeds the tourist industry, which creates revenue for the government, more than compensating for the subsidies given to the Arts. Denys Lasdun had been appointed as architect for the IBM building, and designed a very similar building to ours, which was going to be built literally next door to us. There was horror at the Board, and indeed throughout the theatre, that a structure which is almost a duplicate should be placed so close to us. In spite of all the representations made, the building finally went ahead. I personally feel it makes a good companion building ‘Amadeus’ opened on November 2nd. When it transferred to the commercial theatre, there was an outcry, that Peter Hall should be personally receiving a percentage of the box office receipts for a work, which was created using all the resources of the National Theatre. I personally felt, that since Peter Hall was grossly underpaid for the work which he did at the National, a more equitable arrangement would have been, for the National to receive half the director’s royalties, and the other half to go to Peter. I invited two friends of mine, Bernard Coral and his wife Diane, to see a performance at the National of ‘Richard III’ starring John Wood. Unfortunately, the day before the performance, Bernard, who was the head of the bookmaking firm, Corals, was arrested for alleged breaches of the Gaming Act, which I believe involved the poaching of members of other casinos, to Corals. The allegations were subsequently disproved. However, Bernard had spent the night in custody. Later on that evening following his release, he turned up in his usual ebullient style at the National, ready to see ‘Richard III’. I, feeling rather embarrassed at the ordeal he had been through, said, ‘I am sorry about the choice of play - I don’t suppose you really feel like seeing ‘Richard III’ tonight. ‘That’s alright,’ he said. ‘I should be delighted to see someone with more problems than me.’ 1980 A great deal of browbeating and tearing of hair occurred at a Board meeting late in the year, over ‘The Romans in Britain’ production, which opened to enormous controversy on 16th October, at the Olivier; mainly, because it portrayed on stage, the rape of a Druid by a Roman soldier. The play drew parallels between the Roman occupation of Britain, and the British presence in Ireland. Horace Cutler, one of our Board members and the leader of the GLC, walked out, and threatened to withdraw the GLC’s grant. Fortunately, nothing came of it. Approximately half of the Board felt we should indulge in a form of self-censorship, whilst the other half, me included, considered that if Peter Hall and the associates considered it reasonable, we should go along with it; this was after lobbying many outside opinions. Things came to a head when Mrs Mary Whitehouse asked the police to see it, with a view to prosecuting us. Having seen it, they decided not to. This was not good enough for Mary Whitehouse; she brought a private prosecution against Michael Bogdanov, the director, on the grounds that the play was obscene. Incidentally, she hadn’t seen it herself - she sent her solicitor. After a delay of fifteen months, on March 15th 1982, the case was heard at the Old Bailey, but after three days, the prosecution was dropped. To my knowledge, it was the first time this particular law had ever been tested; if the trial had continued and had found for the prosecution, Bogdanov may have ended up in prison. As far as the critics of the National Theatre were concerned, the whole NT Board should have joined him. 1981 During this year, Max Rayne arranged several caucus meetings, comprising a handful of members of the Board - beautifully catered for, and usually held in one of the private rooms at the Savoy. On one particular occasion, present were Lord Rayne, Lord Chorley, Lord Mishcon, Sir Derek Mitchell and myself. In making polite conversation, Max jokingly looked round, and said, ‘Do you realise you’re the only “mister” here?’ ‘The thought had occurred to me,’ I said. ‘Well, we’ll have to see if we can do something about that’, Max answered. Rather diffidently, I said, ‘Thank you very much’. Nothing happened, then after about three months, Max took me to one side and said, ‘You know that discussion about your being a “mister”, I said, ‘Yes’. Max said, ‘Well, I’ve spoken to the appropriate sources in the government, and they’ve told me they don’t give honours away like sweets.’ Since the thought had never occurred to me in the first place, I wasn’t too disappointed. (Although in the light of fairly recent events, maybe a few quid in an envelope delivered to the right quarter and BINGO). That year Lord Mishcon moved into the basement flat of a building in Wimpole Street; co-incidentally, I was living on the third floor. The word ‘basement’ probably conveys the wrong impression. It had five or six splendid rooms, a garage and a large patio. At that time I was smoking eighty Senior Service cigarettes a day, which meant that each morning when I woke, I would have a coughing fit lasting for about half an hour, until I got rid of all the congestion on my lungs. I thought this was a particularly private affair, but at each and every Board meeting, Lord Mishcon would greet me with the words, ‘I heard you coughing very well this morning, and that was from the third floor’. When Lord Mishcon was considering buying the basement flat in Wimpole Street, he read the lease, and asked for his Chief Clerk to come and cast an eye over it, saying, ‘I think this is very onerous, tell me what you think’. His chief clerk burst out laughing. Victor asked, ‘Why are you laughing?’ ‘If I may remind Your Lordship, about twenty years ago, Phil Hyams who owns the building, asked if we would draw the leases of the flats for him - and you, personally drew that one’. Finally, Peter Hall was granted something he had been wishing for ten years. He directed for the Olivier theatre, Aeschylus’s ‘The Oresteia’ as it was originally performed; all the actors had to be in masks made out of timbre. Peter Hall and some of the critics were delighted with it. I found it very long, four and a half hours, and if you will pardon the expression, a trifle wooden. 1982 Proposals were made at a Board meeting, that some of our productions should be televised to earn money; another was, that we should film them for posterity. With this in mind, I thought it would be an idea to have somebody with an in-depth knowledge of the film industry on the Board, and suggested to Max Rayne, that Timothy Burrell, my friend and a film producer, should be invited to serve. Max thought this was a good idea; he spoke to the appropriate people and Timothy was appointed. In order to try to advance the idea of the filming the NT productions, I arranged a meeting between Bernie Delfont, Barry Spikings, members of EMI Film & Theatre Corporation and Peter Hall. We had a very interesting debate, lasting over two hours, but the idea didn’t come to anything, because in essence, if you are filming a stage production, you’ve got limited camera coverage; performances which are necessary for the stage, are totally inappropriate for film. It’s a completely different way of working – projection is all in the theatre; in film, almost nothing is everything – a mere twitch of an eyebrow can sometimes be over the top. However, it would have been interesting to have some of the N.T. plays filmed for posterity, albeit with ‘over the top’ stage performances on film. Peter Hall seems to have been making a few trips to New York on Concorde,(what's he up to ? ) but not, I hasten to add, at the expense of the National Theatre. 1983 Peter Hall had only one ill-fated attempt at a musical – a science fiction story called ‘Via Galactica’, music by Galt MacDermot, book by Christopher Gore and Judith Ross, with lyrics by Christopher Gore, opening in New York at the Uris theatre on November 28th 1972, and closing on December 2nd 1972. It ran for only seven performances. Now, Peter decided it was time to have another shot - this time at the National. I won’t say it was the thought of the royalties which motivated him, but they would have come in handy. I’m sure that subsequently, he must have had the odd sideways glance at the fortunes Trevor Nunn earned, from his musicals. The plan of doing a new musical at the National attracted all the expected comments in the media; the National shouldn’t be doing musicals etc, etc. But why? The National does new plays – why shouldn’t the National do new musicals, if considered to be artistically desirable? If with hindsight it transpires they are not, well, that’s the case with many new projects. This musical was based on the tragic life of Jean Seberg, who, without the necessary talent, was turned into a star, and because of her political leanings and her involvement with the Black Panthers, was hounded by J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI. The resultant stress caused her to commit suicide in 1979. The musical was entitled ‘Jean Seberg’, script by Julian Barry, lyrics by Christopher Adler, with music by Marvin Hamlisch. Although Peter was as knowledgeable as it was possible to be about the legitimate theatre and opera, he was rather tentative about his grasp of musicals. He approached me, and asked if I would come to see a workshop of the musical he was giving, in one of the rehearsal rooms at the National. He had invited an audience of about eighty people, presumably to get their feedback. He took particular care to greet me when I arrived, and led me to a seat he had reserved, which I suppose was equivalent to fifth row, centre stalls. Having watched the piece, I gave him my opinion , but I don’t think it was a great deal of help to him. In essence, I felt the piece was being approached in completely the wrong way, and only a major restructuring would have helped. In other words, a completely different musical to the one I had seen, which was of course, was out of the question. Regardless of the reservations, the production moved ahead, opened on 1st December to poor notices and limped along for a total of 76 performances, including previews. 1984 Following a request from the Board, figures were produced indicating that in the past five years, the NT’s grant had risen by only a third less than inflation. Unless we received a dramatic increase from the Arts Council, we were facing a grave financial crisis. We were informed that our increase in grant for the following year would be less than 10% of what we needed to restore the status quo. I went with Max Rayne, some members of the NT caucus, and Peter Hall, to plead our case to Lord Gowrie, who was then the Minister for the Arts. When we pointed out that the costs of simply occupying the new building were incredibly high before we even employed an actor, let alone stage the production, the idea was floated that it might be much cheaper to occupy an old existing theatre, such as the Lyceum. (This was without considering how much it would cost to reinstate it). Of course we rejected the idea Max Rayne and Peter had diametrically opposed methods for pursuing additional funds. Max preferred to use stealth in the corridors of power and not upset anyone by public debate, whereas Peter preferred sabre rattling, publicizing the whole problem through the media. This certainly got up the noses of most of the establishment, probably Mrs Thatcher in particular. The Board and Peter had agreed that the only way to avoid the deficit was to close the Cottesloe theatre, make a huge reduction in staff, and in addition, not to tour any productions. Peter chose to broadcast this to the media at a press conference at the National Theatre,standing on a table the restaurant.This became known as the 'coffee table speech’ In it he attacked the government, the Arts Council and Lord Gowrie. This public display of anger and recrimination did not sit well with Max or us on the Board, we would have preferred for it to have been handled in a gentler manner. It did however, have the effect of for once, getting not only the media, but also all the other subsidised theatres on our side. We closed the Cottesloe for nearly six months, and at the end of that, to help us reopen it, the GLC gave us a special grant of nearly £400,000. This, together with the big box office successes we’d had, meant that we broke even by April 1986. Our reward for this was that we got no increase at all in grant in 1987. Instead, we were leant on to provide more and more resources from private subsidy. 1985 This was the year of ‘Pravda’. The Board was worried that the characters portrayed might be identified with real people, and the play considered libelous. Peter had warned us of possible repercussions, and in this instance, since we felt we might be ultimately, legally responsible, we asked to read the play; Peter was happy to acquiesce. I personally was enthralled by it, wishing I could have had it as a commercial vehicle. But to my astonishment, at the next Board meeting when it was discussed, most of the members weren’t keen on it, but they didn’t consider it to be libelous; so it proceeded, with a towering star performance from Anthony Hopkins and was an enormous success. During the next couple of years, our increase in grant was less than inflation, forcing us to depend more and more on commercial sponsorship. Fortunately, we had people on the Board who were very adept at raising sponsorship money, namely: Sonia Melchett, Sir Peter Parker and Louis Sieff; they performed admirably. At one of the caucus meetings, I had a disagreement with Lord Mishcon over ‘Guys and Dolls’, an enormous hit directed by Richard Eyre. It had been sold out when it first opened in 1982, and was sold out again when revived in 1984; it was then taken out of the repertoire. I made the point very strongly, that I felt that the general public should be allowed to see this production, and since there was no longer room for it in the repertoire of the NT, it should be transferred to the West End,( In spite of our previous experience with' Bedroom Farce') where the public at large could have a chance to see it. Victor disagreed with me, saying that we shouldn’t occupy the time, efforts, and money of the National Theatre, in staging yet another revival for the West End. I argued that the proceeds which would arise from a West End run, would more than compensate for any minor disruption. As one man, the rest of the caucus meeting decided that Victor Mishcon’s advice was more appropriate than mine. (Well, given his status, it was no more than I expected). I left it for the time being, but I was not prepared to give up on it. I approached a friend of mine, Paul Gregg, and suggested that if he made a good sales pitch to the National, they might be swayed, and if so, I could possibly provide the Prince of Wales theatre for him. Paul being a very astute businessman, made the pitch and the National Theatre agreed. When it was in the planning stage, I heard that Clarke Peters, a black actor, was to play Sky Masterson, the leading role. Clarke was an exceedingly talented performer, and could more than do justice to the part. However, since the period of the musical was set in the early 40s, it seemed completely illogical, that a black man would be accepted among the white gangsters. In that period, a black gambler attempting to seduce a white Salvation Army girl might have risked being shot. At that time segregation was rife, even the US army was completely segregated and black troops were used mainly as support, and very rarely if ever, served alongside white troops. It wasn’t until the 50s that segregation began to break down and in the 60s, the US forces finally became fully integrated. Paul Gregg took my concerns on board, and said to Richard Eyre that he should consider recasting. The upshot of that was that, Richard Eyre talked to Peter Hall, who was still in charge of the National, who then spoke to me, saying they couldn’t recast, and that when I looked at the stage, I shouldn’t see black. My reply was - I couldn’t look at the stage and see 6 feet 6 inches Bernard Bresslaw playing one of the dwarfs in ‘Snow White’. I couldn’t see a two-legged man playing Long John Silver and I couldn’t see a one-legged man playing Tarzan. Nor, could I see Harry Secombe as a survivor of a Jananese concentration camp, I wouldn’t want to see Steve McQueen playing Paul Robeson, Paul Robeson playing Charlie Chan or Charlie Chan playing Steve McQueen. I didn’t get a really satisfactory reply to my comments - but then I didn’t expect one.( I suppose I could have chucked in, why did Olivier black up to play Othello) ‘Guys and Dolls’ opened at the Prince of Wales on 13th June 1985, running for 354 performances. This card was also to be played by Nick Hytner in ‘Carousel’, which was set in a fishing village in New England in 1873. It was not until 1875 that a Civil Rights Bill was passed which gave blacks equal treatment in Inns, public conveniences and diverse places. In 1883, this Bill was overturned by the Supreme Court on the grounds that Congress was making laws only States had the right to make Nick cast a black man as Mr Snow, a New England fisherman and a pillar of the community. Totally out of place once again; he would have found it extremely difficult to be accepted as a member of the establishment,in that society, at that time. Clive Rowe is an extremely talented performer, but when you cast this way, it distracts from the plot, because instead of concentrating upon what the authors want you to concentrate on, you’re thinking, ‘But surely they couldn’t have had a black man in that position in those days? What would have been the reaction of people all around him'? Now if the authors had wanted Mr Snow and Sky Masterson to be black men, they would have written into the musicals the way these two characters came to be accepted into their respective societies, in the face of treatment of blacks at that time in an essentially white community. This would probably have made an interesting addition to the plots, but they didn’t write it that way, and therefore, you are left struggling to work out in your own mind, how this came to pass, and it can distract you. 1986 This was the year in which Peter and Trevor Nunn sued The Sunday Times for libel, over an article which they claimed contained a professional slur. Peter eventually decided to drop the case, since it would have meant ruin him if it had gone against him. Sometime later, Trevor also withdrew from the action, after The Times published an article which could have been interpreted as a climb down. Part of the Peter Hall furore was caused by the so called ‘Yonadab Conspiracy’. ‘Yonadab’ opened on 4th December 1985. This play was written by Peter Shaffer, who’d had such an enormous success with ‘Amadeus’, which was shared by the National Theatre, when it transferred commercially. Sir Peter Hall, who was receiving his normal commercial theatre percentage, was criticised for this, but it must be pointed out, that the National Theatre received as its share, more than three times as much as Peter – over £2m. Prior to Yonadab's opening, the so-called conspiracy alluded to the rumour that the NT was going to receive less from the transfer, in order that Peter Hall could receive more. This was blatantly untrue. The arrangement was that the Schubert Organisation had first call on it from the authors, in the event of a transfer. The Schubert’s were controlled by Bernie Jacobs and Jerry Schoenfeld - the two most important people in New York theatre. Later on, I was to have innumerable meetings and negotiations with Bernie Jacobs in my office in London, over the deal for ‘Chess’ at the Prince Edward, which they were presenting with Robert Fox. As far as the ‘Yonadab’ deal was concerned, the NT board empowered me to be the sole negotiator for the Broadway transfer, if any. Jerry thought he was going to pick it up for a song, and nearly had a fit when I told him we wanted 2.5% of the gross, 20% of the profits, with an up-front payment to cover all the costs of the production, of up to $1m. He was violently opposed to this, and asked for a meeting with the Board which took place. The Board reiterated that I was to be the sole negotiator, and they would support any proposals I made. Whilst I was on a trip to New York, trying to arrange a theatre for Paul Daniels to appear off Broadway, I received a call from Peter Hall’s agent, Sam Cohn, asking if I would see him. I took time to go to his office; he said to me that he was concerned about the deal I was proposing for the show with the Schubert's. I pointed out to him that he should concern himself primarily with the deal which Peter Hall was going to have, and that what the Schubert’s had to pay the National, was nothing whatsoever to do with him. This brought the meeting to a frosty close, but as history tells us, all the attempted negotiations were pointless anyway. The play only ran for 71 performances, including previews.We did have a scare though, when we realised during the run we were going to be short of the mandatory number of performances required in order to acquire the American rights. Extra performances were hurriedly arranged Peter Hall informed the Board that he would be leaving in two years time proposing as his successor, Richard Eyre. This was debated at the Board, and agreed. Nonsensically, the Arts Council insisted that the job be advertised, although we had obviously considered every conceivable option. We didn’t want to advertise the post, but we fell in with what I assumed, were the government’s wishes. There were only four applications; none of them suitable. Richard’s appointment was therefore approved, but he insisted that David Aukin, who had been in the Hampstead theatre, and running the Haymarket in Leicester, was also appointed, to jointly share responsibility with him, as an administrative director. David joined us before Richard took over, but since at heart he wasn’t an administrator, he was a producer, he left in 1990 to go to Channel 4. 1987 It was during this year that Peter launched an attack on Mrs Thatcher’s policies. I personally didn’t approve of this, since for the main part, I believed that the country owed a great deal to Mrs Thatcher. I approached Max Rayne, saying I felt the Board should distance itself from Peter’s attack. If we kept silent, it would appear that we were in sympathy with it. I said that if the Board intended to do nothing, I, personally was going to write to the press as a Board member, to say that I didn’t agree with Peter, and that I was in favour of most of Mrs Thatcher’s policies. Max however comforted me by saying he was in total agreement, and he wrote to the papers, saying that Peter’s views did not reflect the views of the majority of the Board of the National Theatre. 30th May 1987 - Gala Performance for Olivier’s eightieth birthday. Everyone lined up to greet him. I don’t think Olivier knew who half of them were. At the end of the show, he received a standing ovation which seemed to go on forever; he enjoyed it so much, he milked it for all it was worth. We were now approaching the end of Peter Hall’s reign at the National, and Peter decided, that one of the things he had wanted to do more than anything was, ‘Anthony and Cleopatra’; this starred Judi Dench and Anthony Hopkins. The production was a triumph, playing to total capacity throughout its run. Peter had allowed himself twelve weeks rehearsal on this play – why he needed so long – God only knows - but regardless - it certainly paid off. 1988 In 1988, the foyer music was sponsored by Robert Maxwell. Dealing with Robert Maxwell put me in mind of the proverb: ‘He should have a long spoon that sups with the Devil’. The spoon on this occasion must have stretched across the Thames. However, in 1989 when we were offered £175,000 sponsorship from Rothmans, the South African tobacco company, we couldn’t find a spoon which was long enough, and the Board turned it down. Peter Hall’s last three productions were ‘Cymbeline’, ‘A Winter’s Tale’ and ‘The Tempest’ – Shakespeare’s three late plays. There was a blip as far as ‘Cymbeline’ was concerned, since Peter cast Sarah Miles to play Imogen. She was not an experienced Shakespearian actress; although on film she had a magical quality, Peter whilst recognizing her great talent, felt that she wouldn’t be comfortable in the role, replacing her with Geraldine James, who was very successful. During that time, Peter rehearsed the three plays. Since he was leaving shortly, he didn’t want to be bothered too much with the administration side of the NT, so to a certain extent, David Aukin took over the reins. Meanwhile earlier, Richard Eyre had been appointed Director Designate, but was not yet officially in charge. The Board had considered long and hard about what present we might give to Peter, as an acknowledgement of his long service. We finally came up with the idea of a beautifully wooden sculpted love seat, which fitted around the base of a tree. Unfortunately, when it came time to present it, he was separated from Maria Ewing - had no house in the country, and no tree. I’ve often wondered what he did with the love seat. Lord Rayne was pressing very strongly for the appellation ‘Royal’ to be attached to the National Theatre. I suppose he felt it would be recognition of his success as Chairman, over many difficult years. Richard Eyre was very much against it, expressing his feelings strongly at Board meetings. I, for my part, could not have cared less one way of the other, but most of the Board was happy to support Max in his wishes. To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the National, Max commissioned a limited number of medallions to commemorate the event; over a 1,000 in cupro nickel to be given to many people associated with the National Theatre, and approximately 50, in solid gold. Max took great delight in privately presenting me with a gold one, and for some reason, via another source, I received a cupro nickel medallion, so I had two, to reward me for my stay at the National. In April this year - a bombshell. Lord Rayne is to be relieved of his post as Chairman; Mary Soames, Winston Churchill’s daughter, will be appointed in his place. Max was very hurt by this: a) because it happened so suddenly and, b) because he felt he should, when the time came, have been involved in the discussions as to who his successor might be; but the corridors of political power were such, that they were able to cast aside a man who had been such a tower of strength in the creation of the National Theatre, without it appears, giving it a second thought. Mary Soames - a lovely, warm, mother-like figure, with a great sense of humour, but who knew little about the theatre; I doubt she went very often. I was incensed at this cavalier treatment by the government of Max. I spoke to him on the phone, telling him so, and said I was going to resign. What did he think? He told me that he didn’t wish to influence me in any way – that was a matter purely for me. When Mary Soames heard of my forthcoming resignation, she asked me to visit her in her office; she asked me not to resign, saying that it would be seen as a blow to her authority, if it were seen that people were against her appointment. I wavered, and whilst I did want to register my protest, I didn’t wish to be hurtful to this lovely lady; so I stayed. At the first Board meeting she chaired, I watched in silent admiration as this gracious lady conducted the meeting as if she had been doing it all her life. What, I wondered, what was going on under her calm exterior? If it had been me, I would have been terrified. But she didn’t turn a hair. On 1st September, Richard Eyre officially became the Director of the National Theatre. I found him difficult to weigh up at Board meetings. After the ebullience of Peter Hall, I found him rather cautious; I got the impression that he felt he was on a tightrope, and had to be extremely careful, (Peter Hall on the other hand, appeared to be able to turn somersaults on the tightrope, and without a safety net). I never felt any real warmth emanating from him. In fact, I got the distinct feeling that he viewed me with some suspicion – possibly thinking, since for some time, John Mortimer and I had been the only true theatricals on the Board and I was a producer; (Judi Dench and Michael Codron were to join us shortly after), that I might challenge him in some way. This was probably a misconception on my part, but those were the vibes I was getting. Early in his tenure, he had a meeting with Denys Lasdun saying he wanted to redesign part of the Olivier. Lasdun is reported to have called him a barbarian. I believe the point was made that ‘the directors could rearrange the furniture, but the room belonged to the architect’. Earlier in the year, Richard Eyre informed us that he proposed to present a play called ‘Question of Attribution’ by Alan Bennett. The main character was to be the Queen, who was to be played by Prunella Scales. This caused certain members of the Board to almost have kittens, particularly Max Rayne and Victor Mishcon, but regardless of their misgivings and pressure, Richard Eyre refused to yield, and finally, the play was produced. Prunella gave a great performance, and no harm was done. It was all a storm in a teacup; but like many of the storms at the National Board meetings, in teacups or not, they weren’t necessarily minuted. On countless occasions, discussions took place which were off the record and not recorded. Needless to say, these were usually the most interesting. On 27th October we had the Royal Gala Performance of ‘The Tempest’ attended by the Queen and Prince Philip. On 6th December there was a farewell dinner for Max Rayne, which instead of sitting down and enjoying, I videoed the whole thing from beginning to end. Earlier in the evening, I had arranged that the National Theatre blaze out on its electric sign, “Thank You” to Max, which I also recorded as a preamble to the dinner. At subsequent Board meetings with Mary Soames, I always got the feeling we were all sympathetic to her dilemma - that sometimes she might be out of her depth – that we took pains not to say anything which could be construed as embarrassing for her. One endearing thing she did at Board meetings was always to produce and set in front of her, a very large, old-fashioned, wind-up alarm clock. The noise of its ticking could be heard in silent moments, but the alarm never went off. Was it there to remind her not to let the meeting go on too long? Or was it a silent message to the rest of us, not to meander too much? During my time at the National, I tried to avoid the lunches which preceded the Board meetings. On some occasions, I had cause to wish I’d missed some of the plays. In March 1990, we presented ‘Sunday in the Park with George’. I suspect I might be in the minority, but I thought it was definitely a case of ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’. I was a great admirer of some of Sondheim’s earlier works – ‘Candide’, ‘Follies’, ‘Gypsy’, ‘West Side Story’ - but once he decided to move from the popular area, into the more esoteric with ‘Pacific Overtures’, ‘Into the Woods’, and particularly, ‘Sunday in the Park with George’, he left me behind. I’m sure that what he was striving to achieve musically was brilliant, to the more knowledgeable, but personally, I found it to be as obscure as an Einstein mathematical formula. When I finally left the National Theatre on 3rd August 1991, I received a very charming letter from Mary Soames, thanking me for staying on and helping her through her initial ‘baptism of fire’. I wondered to myself how the National would fare with Richard at the helm. In 1987 he had written and directed a rip-off of the film ‘High Society’.I considered it deserved to be on the list of some of the worst musicals I had seen It starred Natasha Richardson, who, whilst being extremely attractive, was to me, devoid of sex appeal. I suppose to a certain extent, this musical counter-balanced the enormous success he’d had with ‘Guys and Dolls’; but that of course, was easy. There was no need to cut or change - everything existed – great book - great songs - no need for any re-writes. I think I could have directed it. He has subsequently directed ‘Mary Poppins’, which I suppose if I was marking, would give him 7 or 8 out of 10 for his contribution. But back to the National Theatre. It did transpire that Richard succeeded triumphantly in picking up the reins from Peter Hall. As a final note, he was left-wing and anti-Royalist. When discussing communism with Max Rayne, Max said to him that his mother had told him that the only true Communist has holes in his shoes, prompting Richard to push his feet further under the table. It should be pointed out, that in spite of his anti-establishment, left-wing feelings – when they he offered him a knighthood – he nearly took their arm off. “We need a National Theatre so badly. There is no theatre in this country at present where young people can see a repertoire of the great classics of the language. It is only in these great plays that the great tradition of theatre can be kept alive. I am very worried for the younger generation. The theatre is in a very serious state of decline.” “Do the English people want a National Theatre? Of course they do not. They never want anything. They have got the British Museum, the National Gallery and Westminster Abbey, but they never wanted them. But once these things stood as mysterious phenomena that had come to them they were quite proud of them, and felt the place would be incomplete without them.”

Subsidised Theatre – A Bargain

|